Diaries and manuscripts turn spotlight on little-known acts of endurance and bravery

From quiet acts of bravery, to overt acts of rebellion, Jewish resistance to the Holocaust took many forms, yet research shows they remain largely unacknowledged in traditional UK teachings about the genocide.

A new exhibition, drawing on thousands of previously unseen documents and manuscripts, is placing some of the little-known personal stories of heroism, active armed resistance, and rescue networks in the extermination camps and ghettos at the forefront.

Opening at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London, it highlights the extraordinary endeavours of Tosia Altman, a courier who as a member of the socialist Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, smuggled herself into Poland’s ghettos on false “Aryanised” papers, organising groups, spreading information and moving weapons, before being captured and dying of her injuries, aged 24, after the Warsaw ghetto uprising in 1943.

“Her story is quite amazing. And she was typical of a lot of the resisters in camps and ghettos. She was quite young, and managed to obtain papers indicating she was just Polish rather than Jewish Polish, allowing her to move around occupied Poland,” said Dr Barbara Warnock, the senior curator.

The extensive diaries of Philipp Manes, who was incarcerated with his wife Gertrud in the Theresienstadt ghetto, in German-occupied Bohemia and Moravia, also features, and contain poems, letters, and drawings from other prisoners, providing a vivid contemporaneous account of the efforts to keep their culture – and humanity – alive in such extreme circumstances.

Manes was key to the cultural life in the ghetto, documenting his experiences in great detail. His final notebook breaks off mid-sentence. On 28 October 1944, he and his wife were sent to Auschwitz, on one of the last transports to leave Theresienstadt, where they were murdered.

“Research by the Centre for Holocaust Education at UCL shows that schools and students in this country aren’t very aware of Jewish resistance. It isn’t taught that much,” said Warnock.

“Sometimes the view that people have is that the Jews didn’t really resist, and people have commented on why wasn’t there more resistance. But in these incredibly extreme circumstances there are just so many examples of resistance, even in the most desperate situations. So the idea there wasn’t resistance is false,” she added.

The exhibition, which runs from 6 August to 30 November, reveals stories of endurance and bravery drawn from the library’s unique archival collection, including witness accounts gathered by its staff in the 1950s.

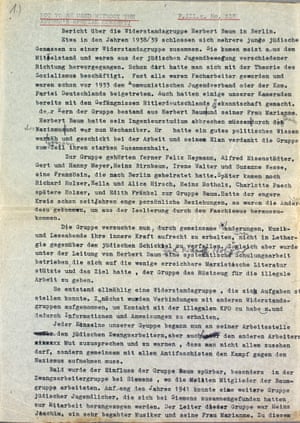

These includes the story of the the Baum Group. Formed by Herbert Baum, his wife and friends, it was part of an anti-Nazi resistance group in Berlin in the 1930s. Almost all of its members were Jewish. Initially motivated by their communist beliefs, from 1936 they also increasingly resisted because of their opposition to the Nazis’ persecution of Jews.

In 1940, after Baum was forced to work at a Siemens factory, he recruited other mainly young Jewish forced labourers to the group, which expanded to about 100 members.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union the following year, they became active in distributing leaflets publicising the the atrocities carried out during the invasion. On 18 May 1942, they carried out an arson attack on the anti-communist and antisemitic Nazi exhibition called Soviet Paradise.Advertisement

Most of those involved in the bombing were arrested and executed. Herbert Baum himself was probably murdered in Moabit prison in Berlin on 11 June 1942. A few survived, managing to escape from captivity, and able to give first-hand accounts to the Wiener Holocaust Library.

“People often when they think about resistance might think of underground groups in France, for example, which they may not be aware contained many Jews,” said Warnock.

“In camps and ghettos, the Nazis’ aim was to destroy Jewish community and lives. People tried to subvert it by continuing with education, social services, religious practices, and by keeping their own diaries even though they weren’t supposed to, so maintaining a sense of their own humanity,” she added.

“There is all sort of resistance, from the armed partisan groups in Berlin, and Paris, but also in Soviet territories where about 30,000 Jews are thought to have joined armed partisan groups, to people writing diaries trying to maintain a sense of themselves.

“There is just a huge variety of different ways Jews responded.”