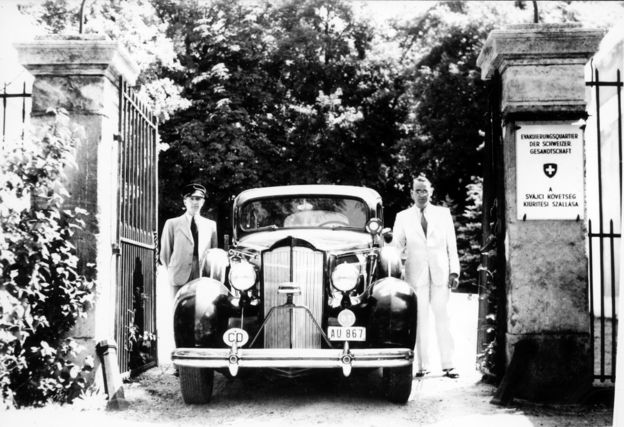

Image copyright Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, ETH Zurich Image caption Carl Lutz in Budapest after arrival of the Russians

A Swiss diplomat has been credited with leading the largest civilian rescue operation of World War Two. But instead of being applauded for saving thousands of Jewish lives, he was reprimanded and – until recently – largely forgotten, as the BBC’s Imogen Foulkes reports.

In a suburb of Switzerland’s capital, Berne, there is a quiet street called Carl Lutz Weg.

Ask people passing by, and no one seems to know much about him.

Read the fine print on the street sign, though, and there is a clue: Swiss Vice-Consul to Budapest, 1942 to 1945.

There are more clues at the Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs.

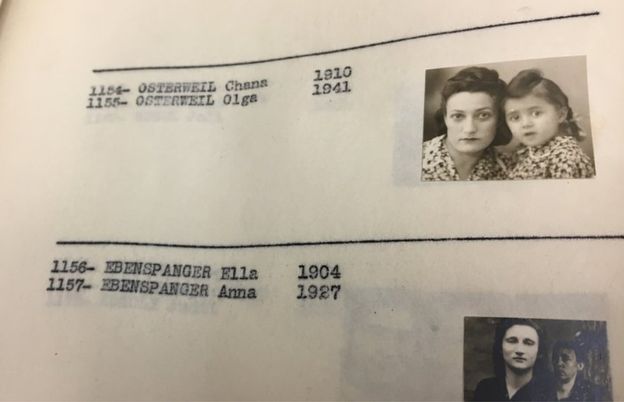

It holds bound volumes containing thousands of letters, each stamped by the government of Switzerland, each with photographs of families. The Geigers: Sandor, Istvan, Eva and Janos. Or the Brettlers: Izsak, Mina and Dora.

They are a record of Carl Lutz’s attempts to stop the Nazis deporting thousands of Jews from Budapest to the death camps.

Switzerland’s Schindler?

A seasoned diplomat, Lutz had served as the Swiss consul to Palestine, then under British mandate, in the 1930s.

He was transferred to Budapest in 1942. Hungary had already joined the war on Germany’s side in 1941, and in 1944 the Nazis occupied the country.

“After the German occupation of Budapest, the Hungarian Jewry in the countryside was in very quick succession deported to Auschwitz,” says Holocaust expert Charlotte Schallié.

“Lutz realised he needed to act very quickly.”

Ms Schallié believes that what Lutz went on to do means he can be compared to Oskar Schindler, the German who saved Jews by employing them in his factories (and who was later immortalised in the film Schindler’s List).

Protective passports

As an envoy for neutral Switzerland, Lutz represented the interests of countries who had closed their embassies in Hungary, including Britain and the United States.

So he began by placing under Swiss protection anyone connected to the countries he represented.

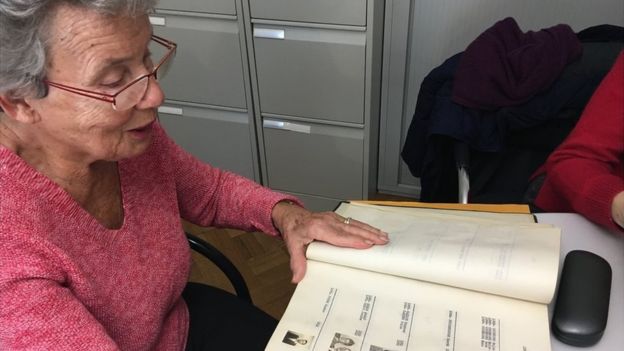

One of them was Agnes Hirschi. She had been born in the UK to Hungarian parents who later returned home to Budapest.

“My mother and I went to the Swiss consulate,” she says.

Image copyright Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, ETH Zurich

“We were all dressed up. Carl Lutz was there at a big desk. And he gave me a protective passport.”

But to save Budapest’s Jews, Lutz needed to go further. He persuaded the Germans to let him issue diplomatic letters of protection, 8,000 of them.

He then applied the letters not to individuals, as the Germans had intended, but to entire families. And once he reached 7,999, he simply started again at number 1, hoping the Nazis would not notice the duplication.

Historians estimate the letters saved up to 62,000 people.

“It is the largest civilian rescue operation of the Second World War,” says Charlotte Schallié.

Other diplomats learnt from Lutz’s methods and did the same – chief among them was Swedish envoy Raoul Wallenberg.

Lutz’s efforts frustrated Nazi officials in Budapest so much they requested permission from Berlin to have him assassinated – although this was never carried out.

Safe houses

As it became clear that Germany would lose the war, Nazi operations in Hungary became more and more brutal.

Rather than organise deportations, they began taking Jewish families to the banks of the River Danube and shooting them.

In response, Carl Lutz set up 76 safe houses. Technically in Switzerland’s territory, the shelters took in thousands. Sweden and the Red Cross set up safe houses too. Altogether there were 120 across Budapest.

Agnes Hirschi remembers taking shelter in the Swiss consulate itself in December 1944, as Budapest braced itself for a bloody battle with the Soviet Army.

“I celebrated my seventh birthday in that cellar,” she says.

“And Carl Lutz was a very nice man. He had some chocolate for me, which he had saved.”

Carl Lutz and many others spent two months in a cellar

Budapest was pounded for two months.

“The Russians came down to the cellar, and they were terrible-looking men,” says Agnes.

“For weeks they didn’t shave and they didn’t wash.

“They wanted watches, and they wanted alcohol. They even drank the eau de cologne of my mother.”

Agnes could finally leave the cellar in February 1945, when the Battle of Budapest ended in Soviet victory.

Bitter homecoming

For Carl Lutz, the war was over, and he was ordered back to Berne.

But the arrival in Switzerland was a shock. Lutz had expected to be welcomed at the border.

“The huge disappointment was that there was no-one,” he remembered in an interview shortly before his death in 1975. “I was just asked, ‘Do you have anything to declare?'”

Far from being commended for his bravery, Lutz was reprimanded for overstepping his authority.

“No one thanked me, they just told me I was lucky to survive the war. No government minister even shook my hand.”

Carl Lutz and his driver in Budapest

Why was Switzerland so churlish? One initial reason: the Russians had arrested other Swiss diplomats in Budapest, and the priority was to get them back. Another, says historian Francois Wisard, is a Swiss aversion to celebrating heroes.

“In Switzerland you do not like the cult of personality. Other countries may have more of this. I think what he did was quite extraordinary, but I am reluctant to use the word hero.”

Neutrality comes first

But the key reason is Switzerland’s neutrality. As the Cold War began, and for decades afterwards, acknowledging Lutz’s actions, however heroic, did not fit the Swiss determination to be completely neutral at all times.

Still, the Swiss diplomat did find some happiness in the ruins of Budapest. After the war Carl Lutz married Agnes’s mother, and today Agnes still works to keep alive the memory of the man who became her stepfather.

“I think he was a hero,” she says.

“He was a very shy man, it was not necessarily in his nature to do what he did. But he saw the misery of the Jews and he thought he had to help.”

Carl Lutz has been honoured by many countries: Israel, Germany, Hungary, and the United States. Next year a room will be named after him in his old place of work, the Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs.

But still, ask most people in Switzerland about Carl Lutz, and the answer will be “who?”