From Mount Mercy Magazine

Mount Mercy University

Cedar Rapids, IA

Spring 2o14

The story begins nearly 70 years ago in a tiny Polish town during the Nazi occupation. David Thaler is a young man when the Nazis begin persecuting the Jews in Europe. By the end of the Holocaust, Thaler loses his father, a sister and his entire extended family in the brutal acts against humanity. In total, nearly six million Jews are exterminated by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

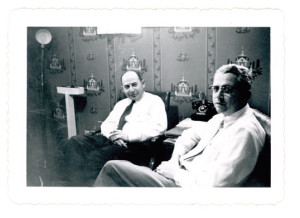

The story continues when David Thaler decides to take classes at Mount Mercy many decades later. By then, he is a retired physician living in Cedar Rapids with a love of learning and a unique story to tell. His classroom experiences and interactions with his fellow students inspire him to plant the seeds for an honors course that literally tells the story of history.

When Monica Schmidt was finishing her academic career at Mount Mercy in 2003, she was a slightly stressed-out senior looking to get into a class she had heard a lot about. While Schmidt and Thaler would never formally meet, the unique course at Mount Mercy started by Thaler and his wife, Joan, offered a platform for Thaler’s story to be told — bringing their worlds together for a brief three-week timespan and forever changing the perspective of countless students. After literally sleeping overnight in her adviser’s office in order to be the first one at the registrar’s desk, Schmidt successfully signed up for “The Holocaust” honors course, a January term class that would bring Thaler’s story of survival during the Nazi Holocaust to life. For an intense three weeks, the multidisciplinary course would change not only Schmidt’s perspective on life, but keep alive the Thalers’ dream.

After completing medical school in France, Thaler immigrated to America in 1938, building a life in the Midwest. He married Joan and created a successful practice as a physician. Upon his retirement in 1985, Thaler re-discovered his passion for learning and along with it, the joys of college life. Thaler, who passed away in 2000, loved taking classes at Mount Mercy and other local colleges and universities. But being back in the classroom with students revealed a startling truth: Young people were forgetting the Holocaust.

“This revelation appalled him,” remembers Mrs. Thaler. “The students didn’t know anything about the Holocaust. That’s when David decided to set up the fund.” The result is the Thaler Holocaust Memorial Fund. The dream was a simple one: The fund was established through Cedar Rapids’ Temple Judah and — with the continued support of the Thalers, the synagogue and the surrounding community — provides funds for area colleges to offer a class on the Holocaust.

The fund also provides an opportunity to bring a Holocaust survivor to the community every year to recount their remarkable experiences during an annual lecture. When the Thalers approached Mount Mercy with the idea to begin a class on the Holocaust, faculty members immediately saw the potential to develop curriculum wrapped around a multidisciplinary approach — offering students a depth of content and insight that resonates long after they finish the course. “Most of the courses taught in the Honors Program are interdisciplinary and team-taught,” says Professor Emeritus Jay Shuldiner, who, alongside Professor of English Dr. Jim Grove, developed the curriculum for the course and teamtaught it from 1996 until his retirement in 2008. “An interdisciplinary approach allowed the students to see more sides of this complex issue,” says Shuldiner.

“When we decided to take this on, I don’t think either one of us realized what a challenge it would be, or how much it would impact us personally,” says Grove. To prepare for the course, Grove delved into the material in ways that went beyond the average curriculum-building approach. With support from the Thaler Holocaust Fund, Grove conducted research at concentration camps in Czechoslovakia (Terezin) and Poland (Auschwitz), and at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The more he researched and developed ways to teach the material, the more he realized what a revolutionary course he and others were creating. “It was so intellectually exciting,” says Grove. “It seemed to be the reason you became a teacher.” Team-taught by professors in two different disciplines — history and English — the Holocaust course melds historical accounts and literary theory together in a way that infuses the curriculum with a human perspective. The result is a powerful course that showcases the devastation, inhumanity and reality of the Holocaust, and why it is relevant to students’ lives today.

“It enriched both of us because we were able to understand the subject through each others’ disciplines,” says Shuldiner. “It spurred us to examine how other avenues such as architecture, music, politics, sociology, religion and philosophy were essential components to understanding these historical events.” Early on, the professors recognized the challenge of portraying the reality of the Holocaust while not making the course too pessimistic and foreboding. “There was always that balance,” says Grove. “Too much optimism was not realistic, but if you made it too dark, the students couldn’t handle it.” The sensitivity of the professors provided a safe learning environment that was appreciated by students.

“It was very heavy and overwhelming, but in a good way,” says Schmidt, who graduated in 2003 and currently works as a substance abuse assessment counselor for Spectrum Health Systems at Oakdale Prison. “It was not dismissive of human evil. But that’s life — the class was a realistic portrayal of war and genocide.”

Dan Morgan, a junior criminal justice and English major who took the course last January, also found support in group discussions and collaboration of ideas. “What helped make it bearable was the discussion,” he says. “The ability to break it down and figure out what would be an appropriate response to the situation.” Professors challenge students to understand the deeper issues involved in the Holocaust — to explore the gray areas of human nature and dig into the events not only from an historical perspective, but from ethical, cultural and global perspectives.

“Students have to explore those controversial issues and different perspectives on the Holocaust,” says Assistant Professor of History Allison McNeese, who taught the course in 2009 and this past January with Assistant Professor of English Christopher DeVault. “We’d take on questions such as ‘Why didn’t more people resist?’ and ‘How can the seeming indifference of the world to this horror be explained?’”

Grove agrees. “It forces students to deal with ethical issues of the 20th century.” The multidisciplinary approach also provides a freedom to explore the subject matter through a variety of media — film, literature, historical textbooks, music, poetry and artwork — wrapping students in the thoughts, feelings, emotions and cultural background of those who experienced it firsthand.

“The course integrates the information in a way that makes sense — it’s not just dry information,” says McNeese. “It’s like life. Music and poetry come out of something within us, from something that matters. It’s all history.” Brittney Thomas, a sophomore accounting major from Marion, Iowa, who took the course last January, saw the different platforms as a safe way to digest the material. “We looked at such different aspects, such as videos and music, which helped break up the intensity,” she says. “The literature and poems would help break up the visuals.”

Schmidt recalls watching movies such as Schindler’s List and The Pianist, and reading Maus: A Survivor’s Tale as part of the class. The approach enabled her to absorb the totality of the material in ways that would not have been possible from simply studying a textbook. “A text can describe an event and give lots of detail, but for a visually oriented generation, a video on the same subject reinforces what one has read and personalizes the situation,” says Schmidt.

The course quickly developed a reputation on Mount Mercy’s campus, and when Schmidt was in school it took her two years to find an empty seat. “Everybody should take this class,” says Schmidt. “It’s one of the best Mount Mercy offers.” She credits this class with giving her a perspective she might not have gained otherwise — a realistic view on human nature and a critical approach to ethical decisions that stays with her to the present day.

“The class really changed my perspective,” says Schmidt. “I was studying criminal justice and psychology, and I began to look at ways humans can justify what they do — and I asked myself what separates me from the Nazis…just a different set of circumstances. Perhaps I could be capable of it.” It’s moments of startling discovery like this that make the class worth it, and assure Mrs. Thaler that the reality of the Holocaust remains alive as an example of what happens when power is allowed to go unchecked.

“It’s important that the students are aware of it [the Holocaust],” says Mrs. Thaler. “Not just to ensure it doesn’t happen again, but at least to heighten people’s awareness. I want them to have an idea of the Holocaust being real, and be sensitized to man’s inhumanity to man.”

“The idea that students aren’t really aware of the Holocaust anymore isn’t surprising,” says Schmidt. “History is yesterday, with how fast technology moves. Seventy years ago is forever; people today have such a short sense of history. But it’s part of a college’s job to lengthen that sense of history.”

The continued impact on the students and community members is what keeps Mrs. Thaler striving to find a speaker every year. “I see the students come up to the speakers and give them a hug after they’ve told their stories,” says Mrs. Thaler. “That makes me feel wonderful. When someone is telling you their story, it becomes very real.”

Mrs. Thaler’s passion for keeping her husband’s story alive dovetails with the University’s passion for social justice — creating a course with unique depth and community impact. “Social justice is an important component of the mission of Mount Mercy, and the study of this subject revolves around the deepest questions about how prejudice undermines social justice,” says Shuldiner.

“The reason we teach this course is tied to the values of our mission,” says Grove. “We teach it so that a horror like the Holocaust will never happen again.” Schmidt feels that professors Shuldiner and Grove accomplished that. “Instead of the information washing over us, we were genuinely moved by it,” she says. “And because we were moved, we are more likely to speak out against current atrocities in order to avoid repeating past mistakes.”

Thomas also recognizes the course’s power. “There are so few survivors left [of the Holocaust], they may be gone soon, and so few young people know about it — how else will we prevent it from happening again?”

Schmidt tries to imagine what it would be like to meet David Thaler personally, after taking the class he envisioned and helped to create. “I’d thank him,” she says. “I would thank him for starting the Thaler Holocaust Memorial Fund — he has quite the legacy here.”