By Nina Shapiro

Seattle Times staff reporter

Laureen Nussbaum pulled a 76-year-old diary off a bookshelf in her Wallingford apartment. When her German refugee family lived in the Netherlands during the Nazi occupation, they took turns writing in it.

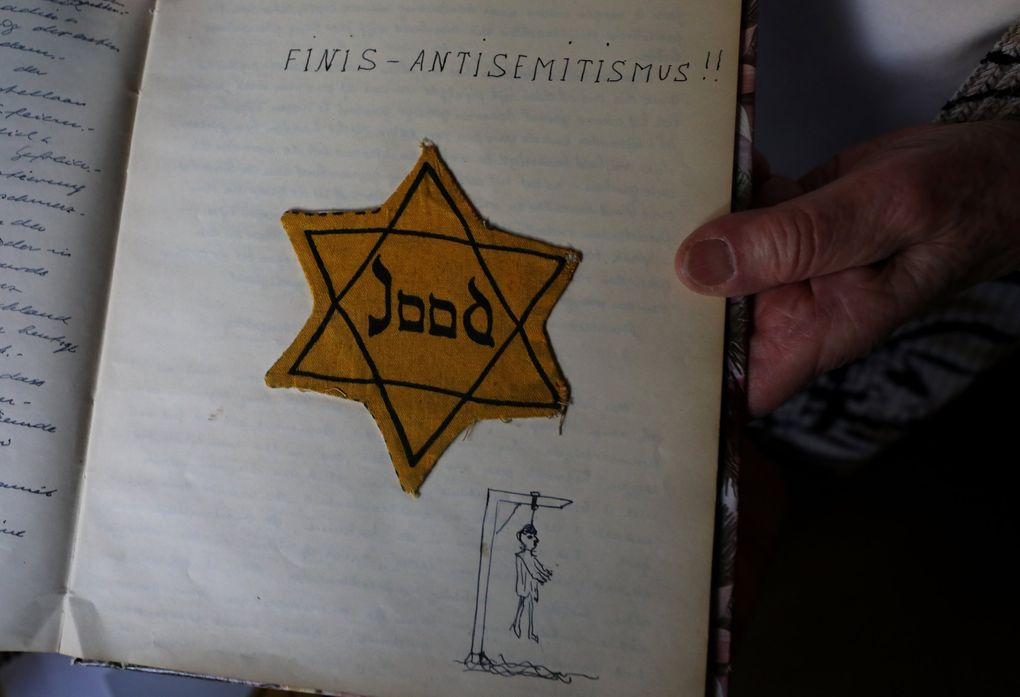

“Finis — Antisemitismus!!” her father wrote as Allied liberators ended the Holocaust. Underneath is the yellow star — branded with the word “jood,” Dutch for “Jew” — he no longer had to wear.

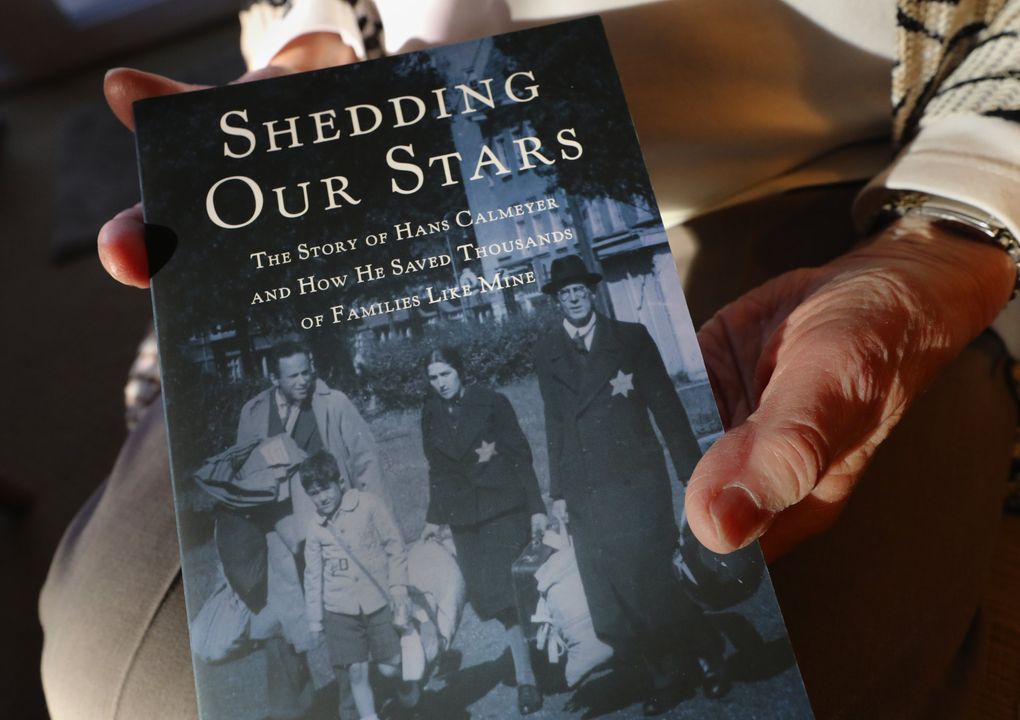

Nussbaum, her mother and her two siblings had been allowed to remove their stars two years earlier. How that came to be is the subject of her just-published book: “Shedding Our Stars: The Story of Hans Calmeyer and How He Saved Thousands of Families Like Mine.”

“It’s so remarkable what Calmeyer did,” Nussbaum said of the German lawyer who used his role in the Nazi bureaucracy to subvert a process of deciding who was a Jew. Everyone knows about Oskar Schindler, she said, referring to the subject of Steven Spielberg’s famous movie “Schindler’s List” who rescued about 1,000 Jews, most working in his factory. Yet few are aware of Calmeyer, credited by the preeminent Israeli Holocaust center Yad Vashem with saving at least 3,000 and by some scholarship, closer to 4,000.

The book arrives as time runs out to collect firsthand stories of Holocaust survivors, and as a rise in anti-Semitism and white nationalism worries many, including Nussbaum.

At 92, the retired Portland State University professor of German language and literature is having quite a year. Not only did she see “Shedding Our Stars” published after nearly five years of work, but she flew to Germany in May to give the keynote address at the launch of another book: a little-known epistolary novel written by Anne Frank when she was in hiding, based on her diary.

Nussbaum, an admirer of Frank’s budding literary talent, advocated for 25 years to get the manuscript published and wrote an afterword. Called “Liebe Kitty” (“Dear Kitty”), it came out in Germany, Austria and Switzerland but can’t be translated into English or distributed in the U.S. until 2047 due to complicated copyright law.

Joachim von Zepelin, co-owner of the book’s German publisher, said he couldn’t believe Nussbaum’s energy during her visit — especially when, after a long day of media interviews, she hopped on a train from Berlin to Hamburg to appear on a popular talk show and didn’t get back until 2 in the morning.

She showed some of that energy at the Seattle retirement community where she lives, moving there from Portland to be closer to her children after her husband died eight years ago. The curly-haired Nussbaum likes to take the stairs, she said, bypassing elevators to go for coffee.

Born Hannelore Klein, she and her family left Germany for the Netherlands in 1936, when she was 8. They lived in the same Amsterdam neighborhood as Anne Frank’s family, also German refugees. She remembers Anne as vivacious, but older sister Margot — composed, thoughtful, ladylike — was Nussbaum’s role model. “Shedding Our Stars” dwells lightly on the association.

The book is after something else: “to let the world know about Hans Calmeyer,” she said. There have been a few books written in German and Dutch that deal with his legacy, but nothing in English. She started off by translating a German biography of him. She spent about a year and a half on that, she said, before realizing it dealt so much with Calmeyer’s left-wing politics that it wouldn’t be right for an American audience. On the advice of a friend from Portland, writer Ursula Le Guin, Nussbaum turned to a new concept: blending her story with Calmeyer’s.

She used historical research to chart Calmeyer’s uneven career path, from a lawyer temporarily disbarred after being branded a Communist sympathizer to a soldier during the invasion of the Netherlands to the head of an office there that decided questions about whether someone should be categorized as a Jew. According to Nazi law, at least three grandparents had to be Jewish.

Thousands petitioned his office for reclassification. Calmeyer, in the name of thorough research, dragged the decision-making process out as long as possible, delaying deportation to concentration camps. In a majority of cases on what became known as the Calmeyer list, people never went to the camps because his office ultimately decided they were not Jewish, despite documentation sometimes patently false.

The bureaucrat confided at the time to a friend he was trying to prevent more people from being sent to the camps and wrote in a statement after the war that he willfully sabotaged laws he took to be immoral.

And so he accepted a concocted story by Nussbaum’s family about her mother having a Christian father. The man identified was really her mom’s foster father for a time, the real father being Jewish. Because Nussbaum’s maternal grandmother was Catholic — a singer who toured all over Europe and didn’t marry her Jewish lover until 20 years after their child was born — the author’s mother was, officially, no longer considered Jewish. Nussbaum and her siblings were regarded as having mixed blood and her father part of a “privileged mixed marriage.”

The reclassification took the family out of danger, and allowed Nussbaum, her siblings and their mother to reintegrate into Dutch society. Nussbaum’s Jewish boyfriend Rudi was not so lucky. Though his parents were sent to the camps, he went into hiding, survived and later became her husband.

Nussbaum, 17 when the war ended, still has vivid memories of the time, and delved into the family journal to capture details. The book tells how she and her siblings walked 45 minutes to a Jewish school they were compelled to attend before being reclassified; Jews had been ordered to turn in their bikes and barred from using public transportation. “Every day fewer students showed up,” she writes, and those remaining learned not to ask questions.

Nussbaum also relates the day her family was rounded up, among 2,000 Jews, for deportation. They waited in a schoolyard for hours before being let go because of the pending case with Calmeyer’s office.

The tone in this passage, as others, is sober but restrained. Nussbaum, who does not refer to herself as a “Holocaust survivor,” reserving that term for those who went to the camps or into hiding, has a toughness about her.

Of course, she felt fear, she said when asked. “You pulled yourself together,” she said, and looked around for others who might need your help.

The family’s reclassification letter came in 1943, prompting enormous relief. As her book chronicles, though, hardships for all in the Netherlands continued during the war. Rations at one point amounted to 200 calories a day and Nussbaum supplemented her diet with tulip bulbs and beets grown for cattle. Many Christians went into hiding as well as Jews because they were subject to forced labor for the war effort.

“What did you think when Anne Frank’s family disappeared?” Nussbaum, while talking in her apartment, said she is always asked. “We thought nothing. Everyone disappeared.”

Nussbaum said she hopes her book will provide this historical perspective. For many years, she added, her memories seemed unwanted. “I wish you wouldn’t always talk about the war years,” a friend once told her and Rudi. The friend and others in their social circle couldn’t relate, she said.

“So we learned to keep our experiences to ourselves.”

“That has changed 180 degrees,” she said. She regards a 1990 internationally touring exhibit about Anne Frank as a turning point. It came to Portland and Seattle, and brought out Holocaust survivors, according to both Nussbaum and Dee Simon, executive director of the Holocaust Center for Humanity in Seattle.

Interest in survivors’ stories soared, and has remained high as numbers dwindle. Simon says the Holocaust Center for Humanity is trying to get to as many of the estimated 150 remaining survivors in Washington as possible, as well as to veterans who liberated the camps, to take their testimony for the center’s online repository. Many have never told their story before, Simon said.

Nussbaum had a book signing at the center, one of roughly a half-dozen events, including a planned Dec. 8 reading at the Wallingford library. Simon said the 100 or so who came were enthusiastic, and for the executive director, the story hit home. Simon’s mother, born in Czechoslovakia, was half-Jewish and spared from deportation — until she was 14, when so-called “mischlings” were sent to the transit camp Theresienstadt. Mischlings stayed there, watching a constant rotation of others get put on trains for Auschwitz. She tried several times to get on such a train, thinking anyplace was better than where she was, but was turned away by a Nazi officer. She now lives in Seattle.

Nussbaum talked about Calmeyer when she visited Germany this spring, and people were surprised to hear about him, said von Zepelin, the publisher. Germans born after the Nazi regime have often been told by their elders “you couldn’t do anything, there was no space,” he said. “For us, it’s important to see they were wrong.”

Still, Petra van den Boomgaard, who teaches history at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, said she doesn’t view Calmeyer as an unmitigated hero. In a doctoral dissertation on those escaping deportation through his office, she pointed out that he denied racial reclassification requests, too, even though Calmeyer knew people would be murdered.

Still, Petra van den Boomgaard, who teaches history at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, said she doesn’t view Calmeyer as an unmitigated hero. In a doctoral dissertation on those escaping deportation through his office, she pointed out that he denied racial reclassification requests, too, even though Calmeyer knew people would be murdered.

She also noted, though, that protesting the whole system would have gotten him ousted, negating his ability to help anyone. That’s a point Nussbaum makes.

The retired professor closely follows current politics as well as history, and like some others who lived through the Holocaust, is troubled. She cites the 2017 Charlottesville rally, where demonstrators chanted “Jews will not replace us.”

When she spoke at the Holocaust Center for Humanity in October, she said, she felt afraid — for the first time in the U.S. “Some idiot might throw a bomb into the building, who knows.”

“The Holocaust didn’t come out of the blue sky,” she said. “I see parallels that are very, very scary.”

Calmeyer’s resistance wasn’t initially recognized after the war. Seen as part of the Nazi regime, he was imprisoned for more than a year. He eventually returned to Germany and resumed his legal career, working among other matters on reparation requests by victims of the Nazis.

In showing the way he stood up to evil, Nussbaum said, she hopes others will be inspired do the same.Nina Shapiro: 206-464-3303 or nshapiro@seattletimes.com.

See original article from The Seattle Times