Feb. 3, 2022 at 2:05 pm Updated Feb. 3, 2022 at 2:54 pm

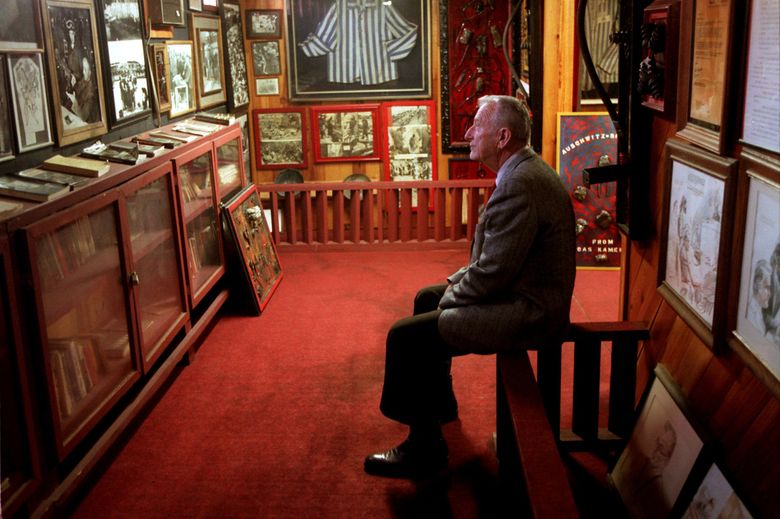

Mel Mermelstein at his Huntington Beach, California, Holocaust museum in 1999. (Robert Lachman / TNS)

By Sam RobertsThe New York Times

Mel Mermelstein, an Auschwitz survivor who, by calling the bluff of self-proclaimed World War II historical revisionists, won a formal apology, $90,000 and a judge’s affirmation that the Holocaust indisputably happened, died last Friday at his home in Long Beach, California. He was 95.

The cause was complications of COVID-19, his daughter, Edie Mermelstein, said.

Mermelstein was 17 in the spring of 1944 when his family was deported from his hometown, then a part of Hungary, to Auschwitz, the Nazi death camp in occupied Poland. His parents and two sisters died in the gas chamber there several months later, and his brother was killed apparently trying to escape.

After the war, Mermelstein emigrated to New York, married and later settled in California, where he started a company that made wooden shipping pallets.

He published a memoir in 1979 titled “By Bread Alone: The Story of A-4685,” the title referring to his prison number.

That same year, the Institute for Historical Review, a newly formed group of Holocaust deniers organized by Willis Carto, a segregationist and antisemite who had previously founded the far-right Liberty Lobby, offered a $50,000 reward to anyone who could prove categorically that Jews were mass-murdered by the Nazis in gas chambers.

When Mermelstein learned of the offer, he recounted his own experiences in letters to The Los Angeles Times and The Jerusalem Post. Undeterred, the institute taunted him to accept its offer, even claiming that his parents and sister were living under assumed names in Israel.

“Dad was incensed,” his daughter told Smithsonian magazine in 2018, “so he went to a lot of established Jewish organizations, and they told him to leave it alone.”

But he was adamant. “I would not let them get away with it,” he said.

As the sole survivor of his family, the lone heir to a legacy of ashes and a living eyewitness to what was now being trivialized and even denied, Mermelstein couldn’t help but remember and refused to let the rest of the world forget.

He submitted a notarized account of watching Nazi guards herding his mother and sisters into a gas chamber. In his book, he recounted his last conversation with his father:

“ ‘Your mother and sisters are … ’ He paused a moment, unable to go on. ‘And you must not torture your minds about their fate. Yes, yes. Look! There!’ And he pointed to the flaming chimneys. The vision of mother, Etu and Magda being burned alive made me feel faint,” he continued. “My head began to spin. I wouldn’t accept it. I wanted to run, but where? I started to rise, but father laid a restraining hand on me.

“ ‘And it’ll happen to us, too,’ he added quietly. Then more firmly he said, ‘But if we stay apart, at least one of us will live to tell.’ ”

The revisionist institute refused to pay the reward, insisting that Mermelstein’s sworn account was insufficient proof. He hired William John Cox, a public interest lawyer (and later in the proceedings, Gloria Allred), and sued in Los Angeles County Superior Court for breach of contract, anticipatory repudiation, libel, injurious denial of established fact and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

Cox invoked two legal issues. One was a technicality that entitled Mermelstein to sue for breach of contract because the back and forth with the institute had been conducted through the mail. The other drew on English common law: “that which is known need not be proven.”

In a pretrial determination, Judge Thomas T. Johnson declared: “This court does take judicial notice of the fact that Jews were gassed to death at Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland during the summer of 1944. It is not reasonably subject to dispute. And it is capable of immediate and accurate determination by resort to sources of reasonably indisputable accuracy. It is simply a fact.”

On Aug. 5, 1985, Judge Robert A. Wenke entered a judgment requiring the institute and several other defendants to pay Mermelstein the $50,000 reward and an additional $40,000, and to issue a letter of apology to him and to his fellow survivors for the “pain, anguish and suffering” caused to them. Mermelstein received the money.

Moric Mermelstein was born Sept. 25, 1926, in Mukachevo, which was then in Czechoslovakia; it was later annexed by Hungary under the Nazis and is now part of Ukraine. His father, Herman-Bernad, was a winemaker. His mother, Fani, was a homemaker. (He changed his name to Melvin when he arrived in the United States.)

His schooling stopped by the 7th grade. The family was deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex once Germany occupied Hungary in the spring of 1944.

In January 1945, as the Germans sensed defeat, Mermelstein was among about 3,200 prisoners forced to march some 155 miles to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, outside a German village (in present-day Poland), where he was loaded onto a train bound for the camp at Buchenwald in Germany. He arrived weighing 68 pounds.

Buchenwald was liberated by U.S. forces on April 11.

Aware of an aunt and uncle living in New York, Mermelstein arrived there in August 1946. He was drafted in 1950 during the Korean War and, rejecting a deferment as a Holocaust survivor, served in military intelligence. After the war the United Nations hired him, a speaker of seven languages, to be a translator.

He married Emma Jane Nance, who survives him along with their daughter; three sons, Bernie, Ken and David; five grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Mermelstein returned to Europe more than 40 times, visiting the sites of the extermination camps and collecting hundreds of artifacts for his nonprofit Auschwitz Study Foundation in Huntington Beach, California. The Chabad Center for Jewish Life in Newport Beach, California, is curating the collection for public viewing.

With his collection, his book, the court judgment and a 1991 TNT film, “Never Forget,” starring Leonard Nimoy as Mermelstein and Dabney Coleman as Cox, Mermelstein fulfilled his father’s hope that “at least one of us will live to tell.”

“I honored my father, mother, brother and two sisters,” he said four years ago. “There are so few of us still alive. I made a big impact for the survivors.”This story was originally published at nytimes.com. Read it here.

COVER PHOTO:

Mr. Mermelstein appeared in this photograph taken at Buchenwald on April 16, 1945, after the U.S. forces liberated the camp. He is seen, his face partly obscured, in the top bunk at the far right. The young man seventh from left in the second row, next to the vertical beam, is Elie Wiesel, who became an author on the Holocaust and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Credit…United States Army