A newly reconstructed document written in 1944 by a Greek Jewish prisoner at Auschwitz tells of misery “the human mind can not imagine.” The text was discovered buried in the ground at the Nazi extermination camp.

Every day, Marcel Nadjari and the other prisoners assigned to the “Sonderkommando” unit at the Nazis’ Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp faced the very worst.

“We all suffer things here that the human mind can not imagine,” Nadjari wrote in a text he secretly penned in late 1944, then stuck in a thermos, wrapped in a leather pouch and buried in the soil near Crematorium III before the camp was liberated in early 1945.

“Underneath a garden, there are two endless basement rooms: one is meant for undressing, the other is a death chamber,” Nadjari wrote. “People enter naked and when it is filled with about 3,000 people, it is closed and they are gassed.”

Unimaginable methods of abuse

The Greek inmate described how prisoners were packed “like sardines” as the Germans used whips to move people closer together before they sealed the doors and let in the gas.

“After half an hour, we would open the doors, and our work began,” Nadjari wrote. The prisoners’ job: delivering the corpses to the crematory ovens, where “a human being ends up as about 640 grams of ashes.”

The rarity and historical importance of Nadjari’s words, which are now almost entirely legible after originally being discovered in very poor condition, makes them very special, said Russian-born historian Pavel Polian.

Nadjari’s message, published for the first time ever in German this month in a quarterly magazine by the Munich-based Institute of Contemporary History (IfZ), is one of nine separate documents found buried at Auschwitz, Polian told DW. The texts, written by a total of five members of the concentration camp’s “Sonderkommando” unit, “are the most central documents of the Holocaust,” he said.

Reconstructing the text

Polian researched the texts for 10 years, and published the findings in his book, “Scrolls from the Ashes.” Such buried messages were found exclusively at Auschwitz, Polian said, “most of them in February or March 1945, right after the camp was liberated.” Nadjari’s was the last to be discovered, he explained, adding that it is highly unlikely any other messages by members of the “Sonderkommando” units are still buried in the ground.

All in all, about 100 of the almost 2,000 Auschwitz inmates tasked with disposing of the many thousands of corpses survived the concentration camp. Of the five who wrote and buried messages, Nadjari was the sole survivor.

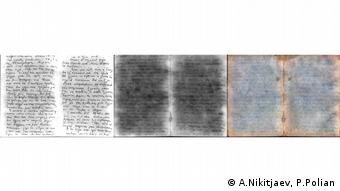

A student doing excavation work in 1980 in the forest near the ruins of Auschwitz-Birkenau’s crematory III unearthed the notes wrapped in the thermos. Unlike the messages by the other inmates, mostly written in Yiddish, only about 10 to 15 percent of Nadjari’s Greek text was legible, Polian said – after all, the paper had been buried in dank soil for 35 years at that point.

The fragile document went to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

In 2013, a young Russian IT specialist spent a year working on the blurred ink script, making the outlines of the letters visible again with the help of multispectral image analysis. “We can now read 85 to 90 percent,” said Polian, who initiated the project. A translation into English and Greek is in the works, he added – scheduled to be published in November.

Surviving the unimaginable

Born in 1917, Marcel Nadjari was a Greek merchant from Thessaloniki. He was deported to Auschwitz in April 1944, and assigned a job with the “Sonderkommando.”

“If you read about the things we did, you’ll say, how could anyone do that, burn their fellow Jews?” he wrote. “That’s what I said at first, too, and thought many times.”

After the war, Nadjari returned to Greece. In 1951, he and his wife and son emigrated to the US, where he worked as a tailor. He died in New York in 1971, aged 54.

While he actually wrote his memoirs back in Greece, it seems the Auschwitz survivor never told anyone about the notes he buried deep in the soil near the crematory, where more than once, he was so devastated that he thought of joining the people in the gas chambers – but the prospect of revenge always held him back.

He is the only one of the five “Sonderkommando” authors who wrote openly about revenge, said Polian, arguing that sets Nadjari’s notes apart from the others.

“I am not sad that I will die,” Nadjari wrote, “but I am sad that I won’t be able to take revenge like I would like to.”