A Jewish teenager avoided death in occupied France thanks to the kindness and bravery of a doctor in a small Alpine resort. But it’s a story local people seem reluctant to remember, Rosie Whitehouse discovers.

As the first snow began to fall in December 1943, Huguette Müller and her sister Marion quietly left the French city of Lyon and travelled up into the Alps, to one of the highest ski resorts in Europe.

The city was no longer safe, as Klaus Barbie – the SS leader who became known as the Butcher of Lyon – had begun to intensify his search for Jews. The two young women pinned their hopes of survival on the village of Val d’Isère, just a few kilometres from the Italian border.

Huguette had already had to flee from Nice, which had been a haven for Jews while it remained under Italian control. But in September 1943, when Italy dropped out of the war, the Nazis swooped along the Riviera making thousands of arrests.

One of them was Huguette’s and Marion’s mother, Edith, seized as she attempted to obtain false papers for herself and Huguette. She was deported in late October and gassed on arrival in Auschwitz – a fact the sisters would only learn after the war.

Aged 15, Huguette had made her way to Lyon, to live with 23-year-old Marion. And now they were both on the move again.

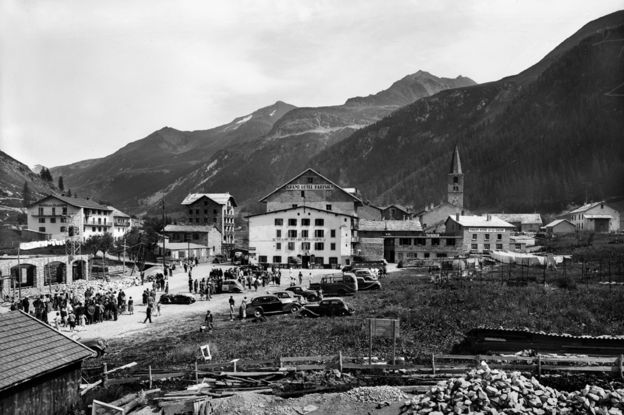

In the winter of 1943, though, the mountains were also a risky place to hide. German soldiers recently relocated from the Russian front were based in Val d’Isère’s Hotel des Glaciers. They pillaged hotels and restaurants and burned chalets to the ground if they found someone who’d been drafted to work in a German factory and failed to go. Locals still refer to the occupation as la terreur.

The SS was also on the lookout for suspicious strangers. So why the sisters went to Val d’Isère puzzles Huguette, now 92. One possibility is that Marion had been advised to go there by her future husband, Pierre Haymann, a member of the French resistance. But they found themselves in serious danger when, not long before Christmas, Huguette slipped and broke her leg.

The village doctor said the break was so bad the teenager needed to be moved to the hospital in Bourg St Maurice, down in the valley. Scared that questions would be asked and their cover blown, Marion panicked and punched him in the face.

On a foggy morning in San Francisco, Huguette takes a sharp intake of breath, and continues telling the story of how she survived the Holocaust, under the doctor’s care.

“I think I was there for six months, I can’t quite remember – all I knew was that it was safe,” she says.

Neither Huguette nor Marion ever spoke about their time in the Alps. Marion waved her hand dismissively whenever asked about it.

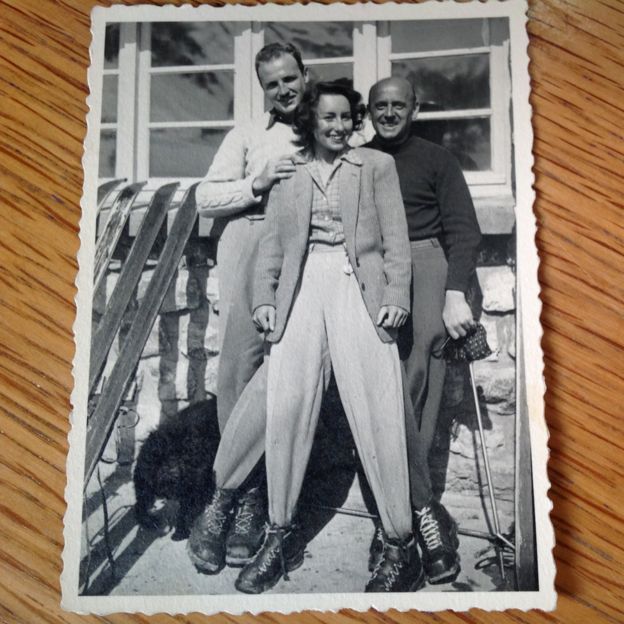

Only one photograph of that period remains. Marion died in in 2010, and as her daughter-in-law it fell to me to empty out her house. In an old suitcase, alongside her wartime papers, there was a picture of her standing next to a mountain chalet in the snow.

It’s only now, 76 years later, that Huguette has decided that she wants her story to be told.

Both sisters were born in Berlin in the 1920s and fled to France from Germany with their parents in 1933, soon after Hitler came to power.

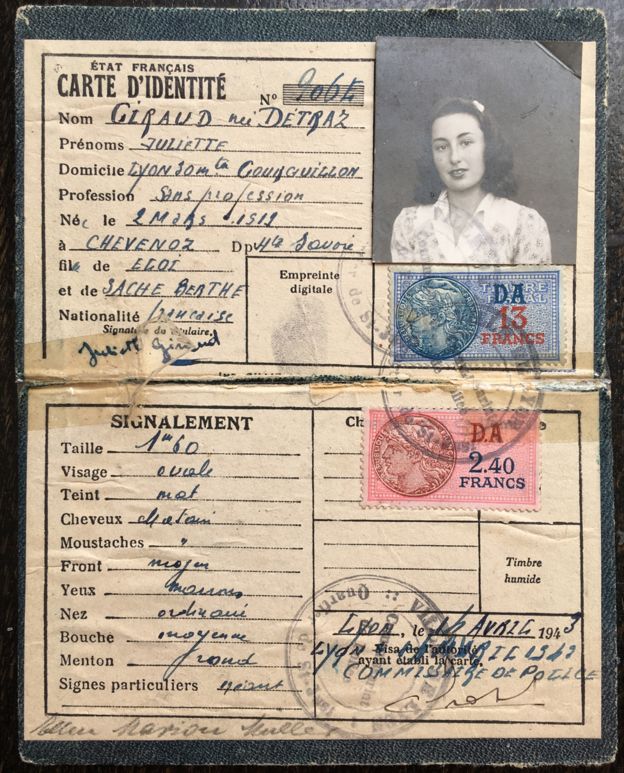

While Marion had false papers, Huguette did not. Their parents had been careful to get her baptised, so there was no telltale J for Juif on her carte d’identité but it did say she had been born in Berlin. That would have been enough for her to be arrested and sent to her death on arrival at the hospital in Bourg St Maurice.

Huguette says the doctor explained that without the right medical care she would end up with one leg shorter than the other. “I replied it was better to limp than be dead,” she says. So, remarkably, he offered to care for her, for six months, in his own house.

Why a total stranger was prepared to risk his life for a teenage girl he had met moments before is a mystery. If he had been caught he and his family would have been imprisoned or shot.

It’s a mystery to Huguette too.

“When I returned to Val d’Isère in the 1970s to find him and thank him, it was too late,” she says. “His widow answered the door and said he was dead. That was that. And now I can’t quite remember his full name.”

A quick Google search reboots her memory. It reveals his name in seconds. The main roundabout in Val d’Isère is Rond-Point Dr Pétri. The doctor, Huguette confirms, was Dr Frédéric Pétri, who lived in a large chalet with his mother and sister. “He was very nice,” she says. “He carried me into the garden when the weather got better.”

A genealogy website reveals that Pétri went on to become mayor of Val d’Isère, welcoming royals and celebrities to the slopes, among them Princess Anne and the Empress of Iran. But he never mentioned to anyone that he had hidden and nursed a Jewish girl during the war.

His daughter, Christel, is not surprised by the revelation. “He was driven by a passion, not for plastering broken legs, but for caring for people,” she says. “He was profoundly generous and all his life he did everything he could for others.”

Today, Val d’Isère stretches for three miles along a narrow mountain plateau, but in the 1940s it was a tiny place with fewer than 150 residents. “My father’s house was on the main street,” she says. “To hide a Jewish girl was a very dangerous thing to do.” Christel is also surprised that the sisters chose to hide in such a small place. The answer she thinks lies in why her father came to Val d’Isère in the first place.

In 1938, passionate about winter sports, the young doctor decided to join his friends, among them world-class ski champions, who had founded the resort a few years earlier. Like many of the young men who ran the hotels and ski schools, he was born in Alsace, a region of eastern France that before World War One had been occupied by the Germans. Christel believes this instilled a dislike of Germany that was only reinforced by the two years he spent in a prisoner of war camp near Stuttgart, from 1940 to 1942.

When the Germans arrived in the Alps in September 1943, the young men and women of Val d’Isère turned the best weapons they had against them – their skis. Adept at crisscrossing the mountain passes they set up a resistance network. One of the group was Germain Mattis, a local ski instructor who was arrested by the Germans in June 1944 and died in a concentration camp at the age of 27.

This may well be the reason that Marion selected Val d’Isère as a place to hide. Her future husband Pierre Haymann was not only a member of the resistance but his family was from Alsace. He may have had connections in the resort.

Trusting the doctor, Marion left her sister in Val d’Isère to recover and went to join Pierre in Toulouse. The break would take six months to mend, so it was not until June 1944 that she returned. Now pregnant, she narrowly avoided being raped and murdered by the SS on the way.

Hoping to learn more about resistance activities in Val d’Isère, I sent a number of emails and left posts on the resort’s Facebook page. I got only one reply, from a member of a famous Paris hairdresssing dynasty – Roby Joffo – whose uncle, Joseph Joffo, wrote one of France’s best-known Holocaust memoirs, A Bag of Marbles.

Roby’s father, Henri, and his uncle Maurice (Joseph Joffo’s elder brothers) were also lying low in Val d’Isère during the winter of 1943-44, though they felt secure enough to work in a hair salon on the main street, opposite the Pétris’ chalet. The Pétri and Joffo families have remained close ever since.

Roby is adamant that there were other Jews hiding in the valley. He makes a number of calls to Val d’Isère, but nobody seems to know anything about it.

The Holocaust in France

About 75,000 Jews were deported from France to concentration camps and death camps between 1940 and 1944. Only in 1995 did French President Jacques Chirac acknowledge French responsibility. “These dark hours forever sully our history and are an insult to our past and our traditions,” he said. “Yes, the criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French, by the French state.”

Only two French officials were convicted for crimes against humanity. One was Paul Touvier a local intelligence chief who served under Lyon Gestapo boss Klaus Barbie; he was convicted in 1994 for having ordered the execution of seven Jews 50 years earlier. The other was Maurice Papon, jailed in 1998 for his role in the deportation of 1,690 Jews from Bordeaux. (Papon had gone on to serve as Paris’s police chief and as a government minister.)

Barbie himself, a German, was extradited from Bolivia to France in 1983 and convicted on 41 counts of crimes against humanity in July 1987.

Christel is not surprised by the eerie silence. She says no-one ever spoke about what happened during the war, and as a result even the families who still live in Val d’Isère today have no idea that members of the French resistance operated in their town.

The war divided communities, explains Jane Metter, who researches the period at Queen Mary University of London. For those who collaborated and those who resisted “the only way to carry on living with your neighbours after the war was to forget what had happened.”

For Frédéric Pétri to have hidden Huguette was, she says, “a 100% dangerous thing to do” and an act that would not necessarily have been applauded after the liberation either, as “the region was a highly Catholic, conservative, right-wing society”.

The archives in Annecy, not far from Val d’Isère, are full of letters written to the authorities during the war, often anonymously, denouncing people for acts of resistance.

Two months after the sisters left, Val d’Isère was liberated. But the local resistance carried on the fight, supporting the partisans in Italy, which was still occupied by the Germans. Once again Petri would place his life on the line for a total stranger. On a winter’s evening in November 1944, he set off to rescue a group of British soldiers who had been led over mountain passes by the partisans. Trapped in a snowdrift without adequate clothing, they were freezing to death.

When Pétri finally found them only one of the soldiers, Alfred Southon, was still alive. He was barely breathing but Pétri refused to give him up for dead. He carried him back to his chalet, and with the help of his mother, cared for him until he was well enough to leave.

This was also a potentially unpopular move as many people resented what they saw as Britain’s abandonment of France at Dunkirk and the bombing raids on French cities. Just as Dr Pétri had said nothing about hiding Huguette, he did not mention this adventure to his family either, until Southon became a celebrity in the UK when his story was told in a 1953 BBC radio documentary.

Marion married Pierre and after the war they settled in Paris with Huguette and their two small children, Francois and Sylvie. The marriage did not last and Marion then began what she called her “second life” in London with husband Joe Judah, and their son Tim (my husband).

In 1947 Huguette went to San Francisco to join her father who had survived the war under cover in Paris. There she fell in love with James Carleton and had a son, Norman. She has lived there ever since. A silver coffee set that once belonged to her mother sits in pride of place on the sideboard in her elegant home.

Huguette now wants Pétri’s bravery and kindness recognised and so I agree to write to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem, to ask if it will consider recognising Pétri as one of the Righteous Among Nations – a list of non-Jewish individuals who risked their lives to help Jews during the Holocaust.

Yad Vashem advises me it could take years for a decision to be made.

I also try to arrange an interview with the mayor of Val d’Isère, Marc Bauer, to ask him to comment on the Yad Vashem application. When I get nowhere by email I telephone the town hall, where a member of staff tells me it will not be possible, as this is a “delicate matter”.

The history of World War Two still haunts France. Huguette’s decision to revisit the darkest period of her life has offered Val d’Isère a chance to address its past, but it appears it isn’t one the resort is ready to take.

You may also be interested in:

A British lawyer is accusing the German government of violating the country’s constitution by refusing to restore the citizenship of thousands of people descended from victims of the Nazis. He argues that the law began to be misapplied under the lingering influence of former Nazis in the 1950s and 60s, and that it’s still being misapplied today.