When Michael Bornstein was just 4 years old, he stuck his arm out to show his identification tattoo to the Soviet soldiers who were liberating Auschwitz.

One of the youngest recorded survivors of the Nazi death camp, Bornstein had undergone more horrors in the first few years of his life than many people endure in a lifetime.

Auschwitz was a place of torture, starvation and death that quite literally filled the air in the form of ashes from the crematoriums, often falling like morbid snow. The camp claimed the lives of Bornstein’s father and older brother and left Bornstein with malnutrition that made all his hair fall out.

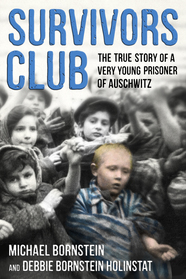

When the Soviet soldiers came to set the survivors free, they filmed the prisoners to show the wider world the atrocities they found. An image they captured, of Bornstein and other young children crowded together in their stripped uniforms, hangs on a wall of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Decades later, an adult Bornstein lived in America with a career, wife, children and grandchildren. He rarely talked about those nightmare days, even when his children asked or people noticed his tattoo. Then his nephew Jacob told him he wanted to educate people about the Holocaust for his bar mitzvah project. Bornstein wanted to help, but it still was difficult to relive the moments he remembered, and he was so small when it happened that there was much he couldn’t recall.

Then one day he saw a still frame of him and the other children survivors on a Holocaust denial website. The site claimed that if children could survive Auschwitz, it must not have been the horrific place people claimed it was.

“Survivors Club,” by Micheal Bornstein and Debbie Bornstein Holinstat.

Furious that his image and story were being used by Holocaust deniers, Bornstein decided it was time to speak. His daughter Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, a journalist, set out to help him.

However, it couldn’t stave off the Nazi death machine forever. Eventually the Jewish ghetto was emptied, the inhabitants sent on trains to concentration camps. Bornstein, his parents, brother and paternal grandmother were first sent to a work camp in Pionki, Poland, and then later to Auschwitz.

At Auschwitz, he first spent his days in the children’s barracks, either struggling to hang on to scraps of bread or swallow mouthfuls of soup from the meager rations before the older children — who also were starving — could steal the food. His mother, realizing he wouldn’t survive on his own, then sneaked him into the women’s barracks, where he had to constantly hide from guards under piles of straw.

Later the family learned Bornstein’s father and brother had been sent to the gas chambers, and then his mother was sent to another work camp. Bornstein and his grandmother Dora were left alone together.

On Jan. 18, 1945, Nazi soldiers, fearing the advance of Allied troops, drove 60,000 prisoners out of Auschwitz on what was dubbed a death march, with tens of thousands perishing on the road, dying of starvation, exhaustion, exposure or simply from being shot if they walked too slowly. Bornstein and his grandmother would not have survived, he wrote in his book. But he had come down with a high fever the day before, and the two were in the camp’s infirmary when the march started. A doctor took pity on him and let him and his grandmother stay behind. Soon after, the Soviets arrived and set the remaining 2,819 prisoners free.

“I think I was very lucky … There were a number of miracles that saved my life,” Bornstein said.

After the war, he and his grandmother made their way back to Zarki, only to find someone else living in their former home. They ended up sleeping in a chicken coop, as one by one the surviving members of their extended family — some of whom had hid in attics for years — made their way back home. Dora told her grandson his mother probably was dead, but he held out hope — when she was sent away, she had promised to come back to him.

And then, one day, she did. That was another kind of miracle, and it’s one that Bornstein said has shaped his outlook ever since.

“Just be optimistic,” he said. “My mother gave me a watch with Hebrew writing that says, ‘This too shall pass.’ Think about the future.”

In 1951, he and his mother emigrated to America after first moving to Germany. Bornstein said even then, their struggles didn’t end, as they essentially were homeless when they first arrived.

“It’s been a tough ordeal. Both in Poland and Germany, there was a lot of discrimination against Jewish people,” he said. “Then in the United States, there was a lot of discrimination.”

Still, he looks at his family and has hope — his life and theirs are a kind of triumph.

“Two generations after the Holocaust, from one survivor, there are four children and 11 grandchildren,” he wrote in “Survivors Club.” (Another grandchild has since been born). “There are hundreds of thousands more from other survivors and escapees. Hitler did not wipe out a religion. Today, our sense of identity is stronger than ever.”

l Comments: (319) 398-8339; alison.gowans@thegazette.com

Michael Bornstein and his daughter Debbie Bornstein Holinstat will speak at four events open to the public this week. More details available at holocausteducate.org.

original post from the Gazette