Ahead of participation in state Yom Hashoah ceremony, 96-year-old who beat Auschwitz and two other camps says, ‘We must tell our story and keep memory alive’

By RENEE GHERT-ZAND 26 April 2022, 10:38 pm

Every year at the Passover seder, Olga Czik Kay reminds her family and friends that in 1944, the Jewish festival of freedom ironically marked the beginning of her slavery during the Holocaust.

A survivor of Auschwitz and the Kaufering and Bergen-Belsenconcentration camps, the 96-year-old Kay is one of six Holocaust survivors to light memorial torches at Israel’s official state Yom Hashoah commemoration ceremony at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem on April 27.

“With people and countries trying to deny the Holocaust, we must tell our story and keep it alive. Soon the responsibility will fall to the next generations,” Kay told The Times of Israel in a recent in-person interview.

On April 15, 1944, 18-year-old Kay and her family were deported from their home in Ujfeherto, Hungary, eventually arriving in Auschwitz on May 22. Two months later, she was transferred to the Kaufering concentration camp in Germany, and then in November 1944, to Bergen-Belsen. Gravely ill and weighing only 25 pounds, Kay was liberated by British forces on April 15, 1945 — exactly one year after being forced from her home.

It was only in 2014 when a granddaughter asked her to participate in a Holocaust testimony educational program called “Names Not Numbers”that Kay began speaking publicly about her wartime experiences. Since then she has spoken on other occasions, including at Zikaron BaSalon (Bring Testimony Home) events in Israel, gatherings at people’s residences at which survivors share their testimony on Yom Hashoah. Kay’s biography and wartime story will be shared at the Yad Vashem ceremony in an audiovisual presentation prior to her lighting the third of the six torches.

“Unlike in the families of many other survivors who did not talk of the Holocaust, from the moment my sister and I could understand, our mom would tell us her story,” Kay’s daughter Judy Cohen said.

Cohen knows her mother’s story so well that she was able to write about it in detail in a book she wrote about her parent’s lives, titled, “Song of the Silent Bell,” published in 2016.

Olga (nee Czik) Kay was born in 1926, the ninth of 10 children in a religiously observant Jewish family. Her father Elek was a shoemaker who had his own store. By the time the Holocaust reached Hungary, the youngest child, Eva, was 16, and some of the older siblings had moved to Budapest for work.

In conversation with The Times of Israel, Kay recounted that a limited contingent of her family celebrated Passover together in Ujfeherto in the spring of 1944: Parents Elek and Lora, sisters Margaret and Eva, Margaret’s little daughter Susie, and oldest sister Bella’s young son Asher (Bella was in Budapest), and Kay herself.

Sisters Adele and Bori were in Budapest, and brothers Zoltan, Miklos, Shanyi, and Erno had been taken to forced labor.

“I remember that we had a pretty normal Passover. We even had matzah,” Kay recalled.

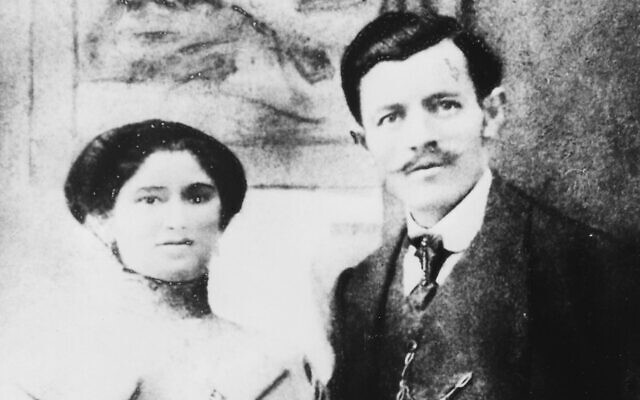

Engagement photo of Olga Czik Kay’s parents Lora and Elek. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

“Then when Passover ended — it was on Saturday night after the Sabbath — the Hungarian police told all the Jews in the town to stay in their homes and not go out. Based on what we had heard, we thought that some people might be randomly arrested, but nothing more than that,” she said.

“We thought that some people might be randomly arrested, but nothing more than that”

By Monday they were still not allowed to go out, and they became suspicious. Then on Tuesday, April 15, 1944, the police came to the family’s door and told them to pack a few things, and they took them to the town hall.

“My sister Margaret wanted to take her fur coat. The police told her to leave it, and that it would be sent to her,” Kay said.

Czik family in Ujfeherto, Hungary. Standing (from left): Adele, Shanyi, Bori, mother Lora, father Elek holding daughter Bella’s son Asher. Sitting (from left): Eva and Olga. This is the only existing photo of Eva, who died at Bergen-Belsen shortly after liberation. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

By evening enough Jewish people had been gathered, and they were walked to a farm in the village of Simapuszta. Kay recalled sleeping on straw in a barn’s animal stalls, and being given water and some food to eat.

“For ‘entertainment,’ one guard made a guy do 25 pushups on his tallit[prayer shawl],” Kay said.

They lived in the barn for four weeks until they were deported on foot to the nearest city, to the Nyiregyhaza ghetto.

“We took nothing with us from the farm, and when we got to Nyiregyhaza we were squeezed into apartments in a building. We were there for 10 days,” Kay recalled.

On May 22, 1944, Kay and her family were deported to Auschwitz. It was a three-day journey by train, packed into cattle cars. When the train crossed the Hungary-Slovakia border, Kay’s father fully understood what their fate would be.

Olga Czik Kay’s mother Lora with her grandchildren

Asher and Susie in Ujfeherto, Hungary.

(Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

“He said, ‘My beloved, we are going to die.’ He took whatever jewelry we had on us and threw it in the bucket in which people relieved themselves. That way, the Nazis would have to reach into urine and feces to retrieve it,” Kay said.

Kay also remembered that when the train pulled into Auschwitz, she wanted to take a pair of stockings she had managed to keep with her. Her father instructed her to leave them behind, saying, “My darling, you do not need those anymore.”

The family underwent a selection, which separated the men from the women. Father Elek was taken first. Then Kay and her younger sister Eva were told to separate from the group and go ahead.

“We ran ahead and looked back to see our family left behind us,” Kay said.

She never saw them again. Her mother, father, sister Margaret, niece Susie and nephew Asher were murdered immediately by gassing. From left: Bella Czik Neuman with her son Asher, two neighbors, Adele Czik, Bori Czik in Ujfeherto, Hungary. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

From left: Bella Czik Neuman with her son Asher, two neighbors, Adele Czik, Bori Czik in Ujfeherto, Hungary. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

Kay and her sister Eva were put into a building with a large room. Surrounded by male and female guards with dogs, they were stripped naked, and their entire bodies shaved. Then they were told to pick a piece of clothing and shoes from a pile.

“We were scared and followed orders. No one knew what was going on. All I remember thinking was that I didn’t get back my nice blue shoes that my father had made for me,” Kay said.

All I remember thinking was that I didn’t get back my nice blue shoes that my father had made for me

The women were then lined up in rows of five and taken to barracks in C Lager (camp) in Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

“People pointed out the crematoria to me, but I didn’t seem them or smell the smoke. I think I must have been in shock and a state of denial,” she said.

Kay and her sister did not work at the death camp, but they had to stand outside, surrounded by guards with dogs, for roll calls that lasted hours. Once a week they were allotted a portion of bread, and once a day they were given what appeared to be a stew of barley with something green in it, which Kay surmised was grass.

She also remembered never having a menstrual period after being forced from her home. None of the women with her had their periods either. It was likely from shock and malnutrition. Like other women survivors, Kay believed it could have been from something the Nazis put in the food. Olga Czik and her sister Bella Neuman are among these Holocaust survivors convalescing at hospital at Lund University in Sweden, August 1945. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

Olga Czik and her sister Bella Neuman are among these Holocaust survivors convalescing at hospital at Lund University in Sweden, August 1945. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

Kay said she and other women were once taken for a real shower. On the way, they passed the infamous “Arbeit Macht Frei” wrought-iron sign at the entrance to the death camp.

“We saw three dead boys hanging from it,” Kay said.

She also once saw a female inmate die on the electrified fence when she tried to catch a kerchief a male inmate had thrown over for her. The woman’s corpse was left on the fence for an entire day.

Eva would not eat, got diarrhea, and was very sick. At one point, Eva and another girl who was a neighbor from Ujfeherto were chosen in a selection. Kay feared for the worst, so she and the other girl’s older sister stayed with the younger girls so they would all be together. They were packed with other women into a large room overnight, with no place to sit or lie down, but in the morning were curiously released back to their regular barracks.

Despite the horrific upheaval, Kay always kept track of the date on the Hebrew calendar. She recalled that it was on Tisha B’Av (July 29, 1944) that she and Eva were transferred by truck to the Kaufering concentration camp complex (sub-camps of Dachau) in Germany.

Clipping from the Newark Star-Ledger from January 1947. A short article on

Olga Czik’s arrival to the city with her sister Bella after they located relatives there.

(Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

Eva and the other younger teenagers were taken daily into town to serve as unpaid maids for German families. At the home where she worked, Eva was fed and was able to obtain food to take back to Kay, who worked piling logs and cleaning the Nazi guards’ barracks.

“Twenty of us were also taken to a field to pick potatoes. I remember fasting for Yom Kippur while I was picking potatoes,” Kay said.

During a British bombing attack, only Soviet prisoners of war who were also in the field were taken to the bunker. The Jewish women were told to go into a nearby building .

“The bunker sustained a direct hit, but the building was fine and the girls came out unscathed,” Kay said.

The next day, in another near miss, a bomb landed a few feet from where Kay stood in the field, but did not explode.

“The field was smoldering, but somehow the bomb didn’t go off,” she said.Olga Czik Kay with her husband George Kay on their wedding day. New York, February 19, 1950. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

Kay was protective of her sister, who broke down emotionally and had crying outbursts. Kay focused on comforting her and avoided falling apart herself, probably from a sense of detachment, or emotional numbness.

“Or maybe I was just more naïve about the situation than my younger sister,” Kay supposed.

The sisters were transferred to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in November 1944. “Riddled with lice,” they were “packed tight like sardines in a box,” lying on the barracks floor. Everyone was sick and did not have the energy to get up and relieve themselves outside. People were dying everywhere.

After some time, Kay and Eva were joined at the camp by their oldest sister Bella and two cousins.

“Bella brought with her a siddur [prayer book] she had been given on her wedding day. That was confiscated and burned. But somehow she was able to keep the guards from noticing her small purse, in which she had family photos,” Kay said.Olga Czik Kay with her husband George Kay and their daughters Evelyn and Judy, New York, 1956. (Courtesy of Olga Czik Kay)

As the British forces advanced, the fighting intensified. Kay recalls having to stay totally still on the ground of the barracks for two weeks to avoid being hit by bullets or shrapnel, as one women near her had.

“I can always remember when a British soldier opened the door to our barracks and said, ‘Everything is okay. You are liberated,’” Kay said.

It was April 15, 1945 — exactly one year since she and her family had been deported from their home in Hungary.

The strongest among her sisters, Kay tried to reach a stockpile of food set up by the liberating forces. She went with some Soviet women POWs, but she was too weak to keep up. She was pushed down to the ground and had to crawl up a wall to right herself. She returned to her sisters without food.Olga Czik Kay’s daughter Evelyn Hefetz with her family. (Courtesy of Judy Cohen)

After having her clothes removed and being sprayed with disinfectant, Kay was given a blanket to wrap around herself. After a week, she was finally given material to fashion into a garment.

Kay and both her sisters were brought to a hospital set up by the Allies at the camp, with Eva, the sickest, assigned to a bed on the first floor. Kay, who was on the top floor, would come down every day to visit Eva.

“One day, I came down and saw that she was only half-covered by her blanket. I went to pull the blanket up so she wouldn’t be cold, and the patient next to her told me she didn’t need to be covered anymore,” a tearful Kay said.

“I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t speak English or German, so I couldn’t ask about giving Eva a proper burial. I can only hope she did not end up in a mass grave, but rather in one of the unmarked individual graves at Bergen-Belsen,” Kay said.Olga Czik Kay with her daughter Judy Cohen’s family. (Courtesy of Judy Cohen)

Seven of the 10 Czik siblings survived the war, all eventually ending up either in Canada or the US. Sisters Bori and Adele were deported together to the Ravensbruck concentration camp and survived by escaping. Miklos survived Auschwitz. Erno survived Mauthausen and went on to fight in Israel’s War of Independence in 1948-1949. Shanyi survived a labor camp in Siberia and made his way back to Hungary in 1948. Zoltan, however, was never heard from again after he was taken to forced labor.

After convalescing at a hospital in Sweden, in January 1947, Kay made her way to Newark, New Jersey, with her older sister Bella to join relatives who had moved to the United States before the war. In 1949, the sisters moved to the Bronx, and Kay worked as a finisher in Manhattan’s garment district. At a dance, she met her future husband George Kay, a fellow Hungarian Jew who had escaped Europe to Palestine in 1939, and arrived in New York in 1946.

The couple was married in 1950 and had two daughters, Evelyn and Judy. Kay stayed at home with the children, while her husband, who had planned to be a dental technician in Hungary, worked as a taxi driver to support the family.Olga Czik Kay holds a pre-WWII photo of her family in Ujfeherto, Hungary, at her home in Shaarei Tikvah, Israel, April 17, 2022. (Renee Ghert-Zand/TOI)

In 1985, Kay and her husband made aliyah to Israel, where their daughter Judy Cohen had been living since 1974. They lived in retirement in Netanya until George died in 2013, at which time Kay joined Judy in the Shaarei Tikvah settlement. Her daughter Evelyn Hefetz lives in Florida. Kay has five grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren in the US and Israel.

Kay said she considers her beloved children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren her revenge against Hitler and the Nazis. She has no tolerance for those who question the Holocaust.

“Every word of what I say is true. There is proof and evidence that it happened,” Kay said.

“How dare anyone deny my experience,” she said.