Lane Sainty and Melina Walling

Tue, February 14, 2023 at 1:31 PM CST·11 min read

When you’ve been married for 68 years, you get used to a certain question: What’s the secret?

“We were just asked that yesterday, actually, by some grandkids,” Werner Salinger said on a recent afternoon in Gold Canyon. “Respect for each other and a willingness to compromise on issues that you might differ on. I think those are the two key things.”

Relationship advice is a dime a dozen, but Werner and his wife Martha might just know what they’re on about. Their relationship was born from the most damaging and destructive of divisions.

Werner is a Holocaust survivor who fled Germany with his family when he was 6. Martha is the daughter of a Nazi soldier, an auditor who was drafted into Hitler’s army.

Their 1950s union was met with family discontent, a series of rabbis who urged Werner to reconsider and pressure to break up from the U.S. military.

In the end, none of that could dim their love.

Fleeing Germany as conflict brewed

Werner was born in Berlin in April 1932, the year before Hitler came to power. His early childhood unfolded under the spreading shadow of the Holocaust.

He was an only child, the son of a secular Jewish couple who lived in the city center. His father was a lawyer and his mother an orthodontist, a “pretty hip lady” who used a hyphenated surname, unusual for a woman at the time.

When he was 3, the Nuremberg Race Laws stripped German Jews like his family of rights. His parents’ client bases were whittled down to Jewish people only, and Werner was forced to move to a Jewish-only kindergarten.

When he was 6, he looked out the window to see the pavement across the street littered with shards of glass, smashed from the windows of Jewish-owned stores. A block away, the synagogue his parents had belonged to was burning, set alight by the Nazis. Werner still remembers the acrid smell of smoke in the air.

It was Nov. 9, 1938, and he had witnessed Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, a pogrom unleashed on German Jews across two violent, hate-filled days.

The Salingers left Berlin two months later. After a brief stay in London and an eight-day boat journey from Rotterdam, Werner and his parents stepped off in New York on Feb. 12, 1939, the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth.

The first year was rocky. Werner attended some of first grade in Brooklyn, where he recalls having an accident in class because he didn’t know how to say, “I have to go to the bathroom” in English. His first American summer was spent at Camp Chickawah in Maine, the trip funded by a Jewish charity.

When summer ended, his mother was gone. She had contracted tuberculosis and died, another seismic shock for young Werner. He was sent to Princeton, New Jersey, to live with his father’s first cousin, Elizabeth, and her husband, a Presbyterian minister and New Testament scholar named Otto Piper.

There, things got easier. Werner was one of eight children in the house — three of Elizabeth and Otto’s kids and five refugees. Otto, whom he called Odo, took the time to teach him English, helping him become an American.

“After the first year, I think it was kind of an almost seamless transition,” Werner said.

It was also in New Jersey that he befriended a man down the street who turned out to be Albert Einstein. Werner got to know the physicist through a connection of his grandmother’s, and he remembers him as a friendly man with windswept hair.

“He loved kids,” Werner said. “And I was just a kid, you know?”

“He would take me by the hand and walk me through his garden, which was beautiful. And then into his study and (he would) pick his violin off the wall for me and play violin for me.”

When he was about 9 or 10, Werner moved to Maryland to once again live with his father, who had remarried to a German woman.

He went to high school in Baltimore and graduated at 17 in 1949, the year before the Korean War broke out. Anxious to repay his adopted country, Werner enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in 1951, choosing it over the Navy because of its new, sky-blue uniforms.

It was a decision that would take him back to Germany and introduce him to the love of his life.

Meeting Martha, writing letters

Martha Herpich was working as a statistician in a small German town called Hof, about halfway between Munich and Berlin.

That’s where some American soldiers were interviewing former prisoners of war to get more information about the Soviet Union.

One of those soldiers conducting interviews with those prisoners was 20-year-old Werner.

It was Werner’s job, along with his squadron, to interview those prisoners to get more information about the Soviet Union. Sometimes they would talk for days, sometimes for weeks, as long as they needed to learn everything they could about how things had been rebuilt.

Then Werner left Hof, transferring 50 miles down the road. But he happened to have a car, a 1938 Plymouth, and he’d organize trips back to Hof on the weekends to go out dancing.

He wasn’t looking for a wife. He was looking for a “pretty young German to see Europe with,” he said.

Then he saw Martha. He was in civilian clothes, though he was supposed to be in uniform, and he spoke fluent German.

They hit it off.

It soon became apparent Martha was more than just a pretty woman to see Europe with, though they did travel. During a stay in the Alps, Werner realized he was in love.

“It was just two people growing closer together with each other in a very important way,” he said. “And it stuck.”

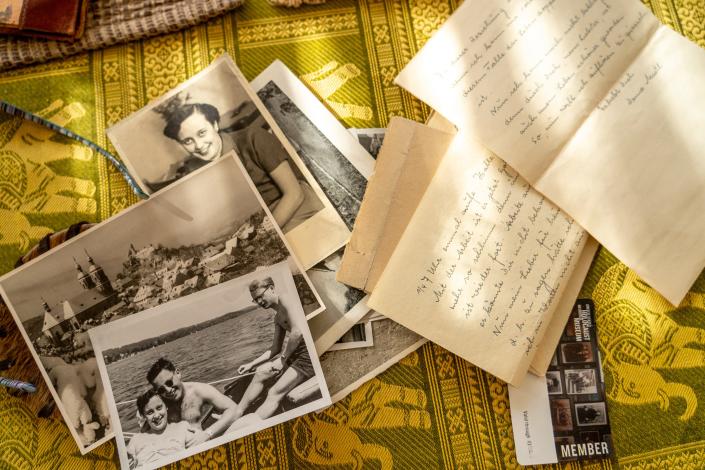

Martha expressed her love for Werner in heartfelt letters that he has kept for all these years.

“I want to say that I have come to know you and love you (at this point we have known each other for three months) as a happy person with a good character,” she wrote. “I hope that our luck and our love does not go away so fast… or even better, never goes away.”

They went on other trips together, went boating on a lake, hung out with Martha’s German friends. And while all that was happening, the couple was contemplating the hurdles they might face if they were to create a future together.

Like, for instance, what their families might think — their parents, who had been on opposite sides of a war.

‘Maybe it will become good for us’

It wasn’t a surprise to the young couple that they might face some opposition to their courtship.

Soon after meeting Martha, Werner made a discovery: Her father had fought in the German army. As a government bureaucrat, he had been drafted and served a couple of years with the occupation forces in France before being sent to the Russian front. There, he suffered a minor elbow wound and was sent back to a hospital behind the front lines shortly before the war ended.

Werner never held it against Martha. “My position always was, you know, she was 12 when the war ended,” he said. “So how could she have possibly had anything to do with the Nazi times?”

This was the logic that he presented to his family as he communicated with them via letter about his new love.

“It was a little rough the first year,” he admitted. They disapproved of his choice.

The situation with Werner’s family was not lost on Martha, who corresponded with Werner in her own letters. She wanted things to work out, but she recognized how difficult the situation was going to be.

“Dear Werner do not make yourself any problems about me — you know what I mean,” she said, referring to his being Jewish as a potential issue for her or her parents.

“If it just doesn’t work, we will just have to part,” she wrote. “You should not have any problems because of me. If that should happen, I will be able to handle it.”

But that wasn’t the only thing working against them. The U.S. military discouraged relationships with German nationals and Werner says they sent religious counselors to try to talk him out of the match.

It was no use. Werner was determined. More than that, he believed his union with Martha was something hopeful, a representation of what it could mean to move past the atrocities of the war.

“From the rabbi’s point of view, it was ‘how could you possibly consider doing this, you know, bringing the daughter of a Nazi family into a Jewish refugee family?’ And I would say to (whichever rabbi had come to me that day), ‘well, that’s exactly what we should be doing,’” Werner said.

At the time, there was a rule that a U.S. soldier could not marry a German national until two weeks before their rotation took them back stateside. That meant there were many months for him to be talked out of the decision, many months during which Martha lay awake at night, wondering whether they would be able to stay together before he went home.

“Oh, Werner, I don’t know if you experience this too, but every night when I am lying in bed I think about us for a long time,” she wrote. “When I think that we just have another nine months (before you return to the United States) I am often very upset. But I also think that many others have gone through this.

“Maybe it will become good for us and we will join in marriage and have a good marriage. Maybe.”

It was never a maybe for Werner. Despite his fraught letters back and forth from America, despite the military rabbis telling him not to, despite the geographical, religious and logistical barriers, he remained firm in his decision.

He felt strongly that he had to face his family first, and so after three and a half years in Germany, he flew back to Baltimore to tell them his intentions.

“(Martha) didn’t know if I was ever coming back,” Werner said. “She and her family had no phone. There were no cell phones or anything. No computers. I couldn’t even call her.”

A week later, on a Sunday, he was back and knocking on her door. He had good news.

By Thursday, they went to City Hall. With her father as a witness, they became husband and wife.

‘Follow your heart’

Their marriage has lasted nearly seven decades. Werner is now 90, and Martha, who let her husband do the talking when it came to their story, will reach the same milestone on Thursday.

Werner has grown used to people asking how his marriage was even possible, let alone long-lasting.

For one thing, Werner’s father-in-law didn’t adhere to Nazi beliefs or politics. He joined the party to keep his job as a bureaucrat and was drafted into the German army. Ideologically, he didn’t support Hitler or the persecution of Jewish people.

To Werner, it’s a meaningful distinction. “If either he or her mother would have been a really avid Nazi, I probably would not have followed up on that whole relationship. I would have gotten out of that whole relationship. But they always welcomed me.”

Besides, he said, “I loved (Martha) for who she was and is and not for whatever political connection.”

As she tells it, her parents were unbothered that Werner was Jewish. Werner’s parents were the harder sell, but eventually came around. In the end, both sides accepted that the young couple’s love could override the pain and division of war.

That’s part of the story Werner relays to children when he visits schools to talk about the Holocaust. He tells them about surviving the conflict and answers their questions about love and marriage. At school and after school, he is asked: “How did you get along with your father-in-law?”

“And I always have a very simple answer for that,” Werner said. “And that is he loved me and I loved him.”

A simple answer, but a complicated journey. In the early days of their relationship, Werner’s Jewish identity was always on their minds. Martha’s letters document their anguish and fervent wish that things could be easier.

In one letter, Martha wrote that a friend of hers and her boyfriend, both German, must have a life that is “twice as good” because they could be certain of marrying without obstacles.

But to Werner, their situation was just another iteration — an extreme one, no doubt — of a somewhat universal issue.

“It seemed to us like an un-overcomeable problem. And I think for most people it would have been,” he said. “Oh, I’m sure there are many other people who face similar problems, racial problems, you know, white girl bringing home a Black boy, a Black girl bringing home a white boy, Mormon bringing home a non-Mormon. Happens all the time.”

His advice to those people, based on 68 years of happiness?

“I’d say follow your heart, not your mind.”

Reach Lane Sainty at lane.sainty@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on Twitter @lanesainty. Melina Walling is at mwalling@gannett.com or on Twitter @MelinaWalling.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: How the daughter of a Nazi soldier and a Holocaust survivor found love