By ELISE DEVLINCHICAGO TRIBUNE |FEB 04, 2022 AT 5:00 AM

If Steen Metz’s willingness to share his story of being a Holocaust survivor had been dependent on face-to-face connections, the Barrington resident’s words might have been lost during the pandemic, which has limited in-person interactions.

But Metz, who was taken alongside his mother, Magna Metz, to the Theresienstadt Concentration Camp in the Czech Republic at just 8 years old, developed an element of tenacity that never left.

And when Metz, 86, learned about online video platforms, he began using the technology to reach others with his story.

“There’s an increase in antisemitism in the world today, an increase in hate,” Metz said of recent events, including incidents in the Chicago area. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s even more important now to learn. I believe education is the major tool to help.

Metz, of Barrington, calculates that he has done presentations for about 94,000 people over the past 10 years, with more than 12,000 of those connections just over the past year, due to his newfound ability to do presentations online. With virtual sessions eliminating geographical barriers, Metz has addressed audiences that would have been impossible to reach. This includes his former high school, Sct. Knuds Gymnasium in Odense, Denmark.

School in Denmark became a place of comfort for Metz after the Swedish Red Cross liberated him and his mother from Theresienstadt on April 16, 1945, when he was nearing his 10th birthday. Seeing familiar faces made him temporarily forget he had been gone. His friends avoided acknowledging that he was absent for 18 months, later revealing that they wanted to let him reflect when ready. Discussing such memories with his audiences has made an impact.

“Instead of just facts and figures, it’s hearing from somebody who has lived through something like this,” said Megan Young, programs and exhibits supervisor at Arlington Heights Memorial Library, for which Metz did a Zoom presentation Jan. 11. “We received a lot of comments about people being humbled and shocked and going through an emotional journey as Steen talked to everyone.”

Metz described his life at Theresienstadt, where he and his mother lived in a loft with 60 to 70 other women and children. His father, Axel Metz, was in a different part of the camp. He said days consisted of lining up for coffee, which he described as boiled water with coffee substitute. They would also receive a loaf of bread to share with the family for the entire week. Lunch was potato soup every day. Metz refused to eat the soup at first because of the taste, but he remembers his mother saying if he was going to make it out, he had to eat it.

Reliving his time at Theresienstadt out loud is not how Metz planned on spreading his Holocaust experiences. In fact, he never planned on sharing his story at all. But when his wife, Eileen Metz, decided to write a memoir, Metz wanted to do the same and was forced to think about his early years.

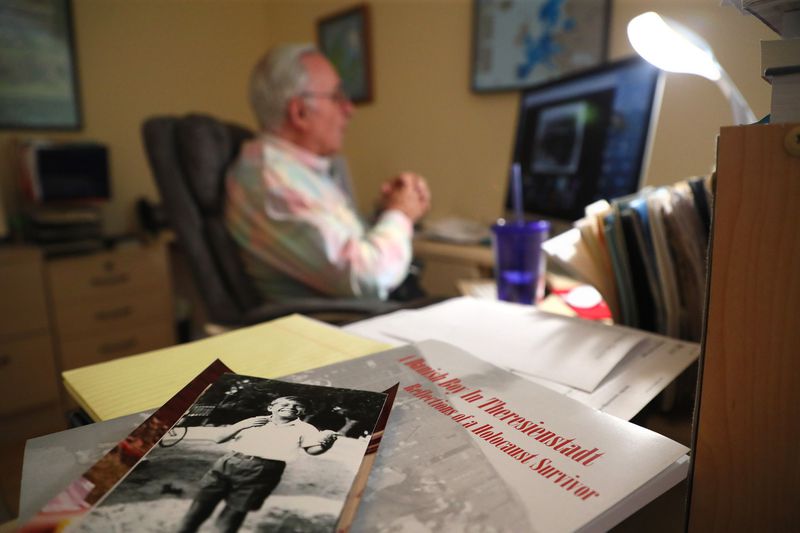

After connecting with people from Denmark and retrieving CDs of his mother’s voice recalling her memories from Theresienstadt, Metz decided he needed to dedicate chapters in his memoir to this time in his life. Later, a friend pushed Metz to publish this part of the book on its own. Metz self-published that material in a book called “A Danish Boy in Theresienstadt, Reflections of a Holocaust Survivor,” and felt his “job was done.” However, others around him, like his daughter Annalise Herman, knew it was not.

“It was always sort of the family secret,” Herman said. “(But) it was my father’s concern that it could happen again. It’s frightening to see how history repeats itself. We don’t recognize when there are hints of it happening again today in other countries and our own country so it’s important to keep (these stories) in the forefront.”

After learning of Metz’s story, a chain of people began pushing him to share the words he had kept to himself for so long. This included Danny Spungen, owner of a well-known collection of Holocaust postal materials from concentration camps and Jewish ghettos. He helps Metz arrange many of his speaking engagements.

“There’s many reasons why Holocaust survivors kept quiet,” Spungen said. “(But) they needed to speak because people can’t forget. But how can we take these stories and get young people to transform the future? To learn from the mistakes of our generation?”

Sarah McDermott, Metz’s granddaughter, has made it her mission to embody this. “It has fully changed how I view the world and who I am as a person, it’s really shaped me,” McDermott said. “It even led me to pick a social justice and inequalities minor in college.”

The pandemic and acknowledgment of his age have created a sense of urgency to talk about the Holocaust for Metz. He knows the number of Holocaust survivors is dwindling. But his family will ensure his legacy lives on.

“It’s been a blessing in disguise because with it being virtual, his talks are being recorded and we’re going to have his story to pass down to generations upon generations in our family,” McDermott said. “Years down the line, I can just imagine my grandkids will be able to read his book but also watch him speak and that to me is amazing.”

To commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27, Metz spoke virtually to students from James G. Blaine Elementary School on Chicago’s North Side. Reaching out to younger audiences like these has become routine, but programs like the speaker’s bureau at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie offer an opportunity for Metz to connect with even more audiences.

“The privilege of hearing directly from a survivor is not something that will happen indefinitely so even if it’s virtually, it’s such an amazing opportunity,” said Amanda Friedman, assistant director of education at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center. “It’s actually enabled the survivors to not only continue to share their stories and their lessons in a way that is safe and less strenuous, but to a significantly larger audience.”

For Metz, reaching a greater number of listeners has helped him achieve his goal of representing those who lost their lives, including his father, who died of starvation at Theresienstadt.

“I was angry, and maybe I’m still angry,” Metz said. “But I’m lucky. I made it. I survived and I’m able to talk to people. That is my revenge.”

Elise Devlin is a freelancer.