Post from independent tribune.com

Gross spoke about his experience as a prisoner at Dachau. He was a laborer and fought starvation and fatigue to survive. He was taken to the camp at 15-years-old. Erin Kidd/jkidd@independenttribune.com

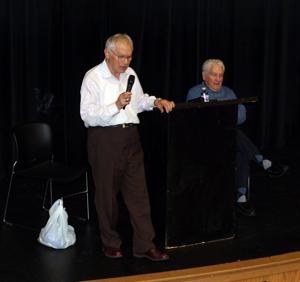

CONCORD- Ernie Gross, 86, held a piece of bread in his hand as he spoke to the audience at Concord High School. He told them a piece of bread like that one was his lifeline when he was imprisoned in Dachau, one of the Nazi concentration camps in Germany during the Holocaust.

At the young age of 15, Gross’ family was deported by the Hungarian government to the Seilish ghetto for three weeks and then to Auschwitz. He lost several family members to the gas chambers and was then imprisoned in Dachau as a laborer until the end of the war.

Gross shared his story with his friend and liberator, Don Greenbaum, at the high school during an event sponsored by the school’s International Travel Club. Gross and Greenbaum are featured in the documentary, “The Liberators: Why We Fought.” The documentary depicts the experiences of men who survived Dachau and American soldiers who liberated the camp on April 29, 1945.

Those who attended the event called “In Their Own Words: Remembering the Holocaust” were shown the documentary and had the chance to ask questions. Many members of the club are traveling to Germany this summer as part of a World War II tour and were eager to meet people who survived it.

“There were 140 people killed by ISIS and the entire world mourned,” Greenbaum told the audience. “But 71 years ago, six million Jews disappeared and nobody cared. That’s why Ernie and I talk about it. We hope our message gets across.”

Don Greenbaum

Greenbaum, 91, served in World War II as a forward observer, operating on the front lines. He said when America entered the war, he was a “real rah rah kid” and couldn’t wait to join the Army and serve his country.

But what he saw in 1945 when his troop arrived at Dachau has never left him.

“The fighting units on the ground had no information on the true nature of a concentration camp. To this day, 71 years later, the odor is still there,” Greenbaum said of the crematorium where the Jews’ bodies were burned. “Every liberator will tell you the odor stays with you.”

Greenbaum earned a Purple Heart in Germany on Nov. 9, 1944 after receiving an injury in battle. When he was released from an Army hospital, he fought in the Battle of the Bulge.

Under the command of General George Patton’s Third Army, he and troops in his divisions were among the first Americans to liberate Dachau. But that was not when he met Gross.

That didn’t come until 60 years later when Greenbaum’s wife Shelley decided to write an article about her husband’s experiences in a local newspaper for Veteran’s Day. She called it “A Soldier’s Redemption.”

“My husband had a friend in the Army that was killed. When he came out of the Army, he never had the courage to call this boy’s family. He felt that if he called the parents, it would bring up bad memories for them,” Shelley said. “I wrote an article about that. There was a line in the article about being a liberator of the camp.”

While Greenbaum was able to meet nephews of his friend who died and make his peace, Gross had been looking for someone to thank for saving his life. He found the article about Greenbaum and set up a time to meet him. Shelley said the two have been inseparable ever since, traveling and telling their stories.

“I have a chance to tell my story and talk about a guy who was 85 pounds when he was liberated at Dachau,” Greenbaum said. “Ernie and I hope by telling our stories, we will educate people so it will never happen again.”

Ernie Gross

Gross said his childhood wasn’t that great and he was not a happy child. He felt he was born in the wrong time and place. As a young child, there were eight beds in his home and nine people, so Gross said he was the leftover and slept with a different sibling every night.

But none of that compared to what happened after April 15, 1944.

Gross told the audience that was the day he and his family were taken away to the ghetto before being transported to Auschwitz.

“I was the last day of Passover, and I went to bed hungry. My mother asked us who wanted to get up early and help her make bread. My brothers didn’t volunteer so it was me again,” Gross said. “The bread was already in the oven that morning when there was a knock on the door. It was two Hungarian police.”

The family was told to leave all jewelry and money on the table and to be at the synagogue in an hour or they would be shot. They were told to leave the door unlocked when they left the house.

After spending three days in the synagogue, the trains arrived to take them to the Seilish ghetto.

“They put three or four families in one house in the ghetto. And then after three weeks, more trains came,” Gross said.

Those trains were bound for Auschwitz, where Gross learned about the gas chambers and crematorium. It was also the last time he saw his parents.

“My father was holding on to my younger brother and my mother was holding on to my younger sister,” Gross said. “They were sent to the left when the trains arrived. That was the last time I saw them.”

Luckily, a prisoner guard pulled Gross aside and told him to tell the Germans he was 17.

“He told me to say I was 17 or you will go with your parents to the left. Then he pointed and said “You see the smoke? That’s going to be your parents.” Gross said. “So I told them I was 17 even though I was 15 at the time.”

Gross and two of his brothers were sent to the right and turned into laborers at Dachau. Then his fight to survive through starvation and fatigue began.

Upon arrival at Dachau prisoners were given a cup which was used for coffee in the morning and a little bit of soup in the evening and one piece of bread to be divided between eight people.

“The way we divided it, we took eight pieces of paper and whichever one you picked, is the piece you have,” Gross said. “I learned that in order to survive you had to be selfish.”

Gross said some prisoners ate their piece of bread all at once and some divided it equally for three meals. But he kept his piece in his pocket and ate crumbs throughout the day, while being forced to work for the German army. He sometimes traded cigarette buds to smokers for a piece of bread.

“It comes to the point where you are not producing enough work because you are so weak and hungry, and when that happens you went to camp seven. There they don’t feed you anymore,” Gross said.

And that’s what happened when the Germans felt the war was coming to an end. Gross and others were sent to camp seven to be exterminated.

“We were getting close enough to see the crematorium. We were tired, hungry and couldn’t wait for it to be over,” Gross said. “Then I saw the guard throw down his weapon.”

On the day that Gross would have been killed, the camp was liberated. Two of his brothers and one sister also survived and they each relocated to different areas of the world. Gross moved to the United States.

A story that needs to be shared

Gross and Greenbaum smiled at each other after the presentation as students asked for their autographs and pictures. The two consider each other brothers and Gross says Greenbaum reminds him of a brother he lost in the Holocaust.

“It took me 60 years to find Don, we became friends immediately,” Gross said. “He is like my brother David. David was almost five years older than me and Don is almost five years older, which has made us closer.”

In the documentary, the two of them and a group of other liberators and survivors traveled to Germany to the Dachau memorial that is now a tourist attraction. There they met with students and told them to continue sharing the story with the world.

“I saw on 20/20 where someone was saying the Holocaust was a hoax,” Greenbaum said. “That is when I decided to start sharing my story. So nobody will forget.”

But Gross tells his story for an entirely different reason that came from his wife Bella, who was also a survivor.

“We never spoke about it. She knew I was a survivor and I knew she was, but we didn’t talk about it. I don’t even know what camp she was in,” Gross said.

Bella died of lung cancer five years ago and Gross began telling his story of survival.

“I realized I was married for 19-and-a-half years and I don’t know anything about my wife,” Gross said. “So from then on, whoever wants to hear me, I’m willing to tell my story.”

Posted: Sunday, April 24, 2016 8:45 pm | Updated: 8:52 pm, Sun Apr 24, 2016.