Lien was one of thousands of Dutch Jewish children hidden from the Nazis by a secret resistance network

In August 1942, a stranger knocked on the door of a house in the Hague, in the Netherlands.

An eight-year-old girl was handed over to the safekeeping of the unknown visitor, to be taken to another town. The girl would never see her mother or father again.

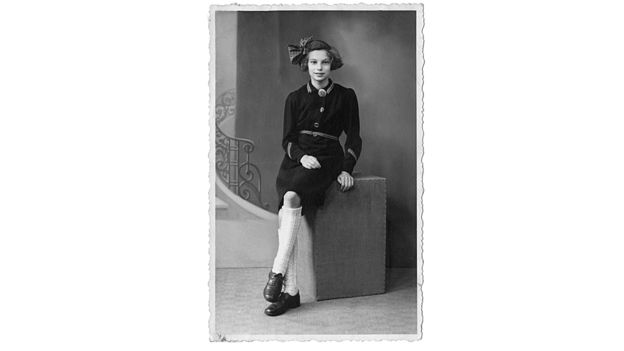

Lien de Jong was a Jewish child under Nazi occupation and her parents had taken the agonising decision to try to save her by losing her.

The yellow stars were unpicked from her clothes and she was taken from her home and disappeared into an underground network of resistance families.

‘Look after her’

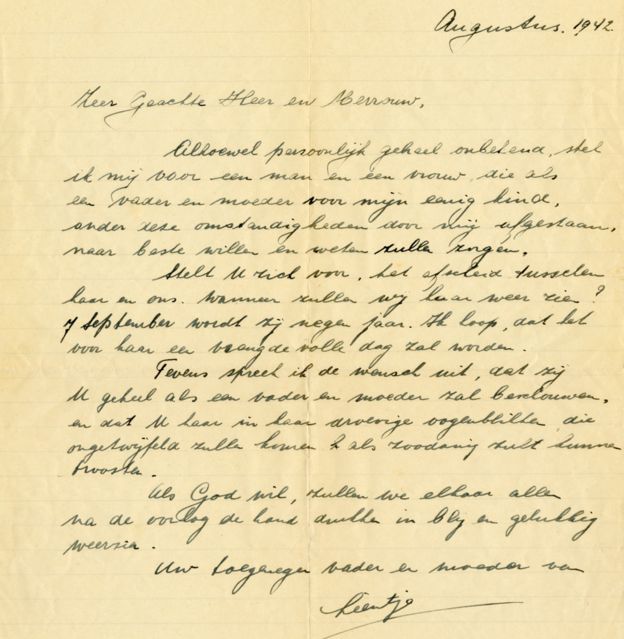

Lien’s mother had put a note into her coat pocket.

“Imagine for yourself the parting between us,” wrote Lien’s mother to whoever would be looking after her daughter.

“Although you are unknown to me, I imagine you as a man and a woman who will, as a father and mother, care for my only child.

A letter sent by Lien’s mother written to the unknown families she hoped would protect her daughter

“She has been taken from me by circumstance. May you, with the best will and wisdom, look after her.”

In August 2018, an Oxford University academic has written a book telling Lien’s haunting story for the first time.

The Cut Out Girl shows how she was one of 4,000 Dutch Jewish children hidden away from the Nazis by non-Jewish families.

The author, Prof Bart van Es, has a personal connection – he is the grandson of the foster parents who risked their lives to protect her.

Secret identities

It’s a story told in close-up and claustrophobic detail.

Lien was passed through safe houses and hidden rooms, living a life of false identities, police raids, escapes and pretending to be someone else’s child in nine different families.

Lien, now 84, survived the War but found it difficult to find her own sense of identity

Prof Van Es says even though his family had been part of these resistance efforts, he found a great reluctance to talk about wartime experiences.

If the topic was raised, he says, his grandmother would “shut it off”.

Lien had survived the War – but had fallen out with the Van Es family who had sheltered her.

And when Prof Van Es made contact with Lien, he began to understand the ambiguities and complexities of the Nazi occupation.

‘I had no idea’

Lien, now 84 and speaking this week on a visit to London, has a clear memory of that last time with her parents and relations – almost all of who were to die in the Holocaust.

“I remember the day,” she says. In retrospect it was the “most terrible thing” but at the time, she says, it seemed almost exciting, with all her family gathered to see her off.

“I couldn’t see what was coming, I had no idea.”

Although there was a long tradition of religious tolerance in the Netherlands, Prof Van Es says, he was “shocked” at how much the Dutch authorities had assisted with the detentions and deportation of Jewish families.

Raids rounding up suspects or hideaways in Amsterdam in 1943

There were efficiency targets and financial bonuses for catching Jews – and a higher proportion of the Jewish population in the Netherlands died under the Nazis than in France, Belgium, Italy or even Germany.

It was an intimate kind of savagery – and Prof Van Es says the willingness of the Dutch police to chase Jewish neighbours was a profound “moral failure”.

Lien says her own experiences showed that in human nature “there is no black or white” and that the same ordinary people “can do good or bad things”.

There were people who behaved with principle, others with pragmatism and some who exploited the suffering of others.

Betrayals

Prof Van Es records a woman who appeared to be a patriotic resistance helper, who shared underground newspapers.

But she was an informer who was sending hidden Jewish families to their deaths.

There were others, says Prof Van Es, who showed “amazing bravery” and an almost “transcendent sense of moral purpose”.

As the Dutch celebrated the end of Nazism, Lien was left without any family or home to go back to

There were rescuers who carried on despite knowing that they would be caught and killed.

Some women ensured the safety of Jewish babies by registering them as their own, and claiming they had been born from affairs with German soldiers.

These women would face being “absolutely ostracised by their own community” and publicly shamed as collaborators and traitors.

Another man who was unable to cope with looking after hideaway children while trying to keep a job cut off his own finger so he could get sick leave and carry on protecting these Jewish refugees.

‘No difference’

There were others who showed a more opportunistic approach.

One of the Dutch policemen who raided a house where Lien was hiding was a notoriously aggressive hunter of Jews.

Lien and Bart van Es, the grandson of her foster parents, who has written her story

As the balance of the War shifted, he became part of the resistance and claimed to have been heroically fighting the Nazis all along.

Not all hideaways were safe. And rescuers were not always good, Lien says.

In one house, she says, she was raped and abused by a relative of the family protecting her.

And such real-life stories do not have tidy endings.

Lien says when the War ended and the Nazis were defeated, “it didn’t make any difference” to her.

“There was no future.” Everything of her old life had been destroyed – there was no scene at the end of the movie where the survivor goes home.

The Westerbork camp where many Jewish families were transported from the Netherlands

“At the end of the War, I couldn’t listen to what anyone was saying. Nothing anyone said seemed important.

“It took me a very long time to realise that my whole family had gone – all my memories.”

Her parents had died in Auschwitz and she returned to the nearest thing she had to a family, the home of Prof Van Es’s grandparents.

Reconstruction

While post-War Holland was rebuilding, Lien struggled to start again.

She married another Holocaust survivor – a classmate of Anne Frank – but there was an unrelenting sense of dislocation and she attempted suicide.

Almost her only surviving wartime relative had also killed himself.

Lien’s childhood had been lost and she had to find a new sense of “belonging”

But it didn’t end there. She trained as a social worker and says she liked to work with children who seemed as lost and rootless as she had felt herself.

“When no-one cares about you, it’s very difficult.”

If not reconciled to her past, she began to face her ghosts.

She had therapy, she wrote about her feelings, she took part in a gathering in Amsterdam of other hidden wartime Jewish children and went to Auschwitz.

She became a mother and grandmother and was back in touch with her wartime foster family.

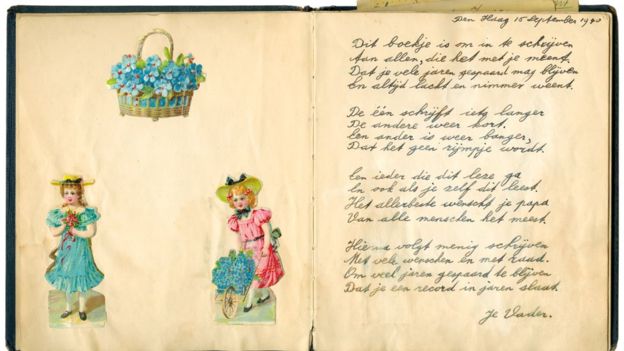

A poem written for Lien by her father before she was taken away into hiding

If she has learned anything from this, she says, it’s the importance of individuals being part of a family and community and having a sense of belonging and shared values.

“It’s very important you have people to belong to.”

Lien talks of her worries about a return of anti-Semitism and intolerance. But she isn’t bitter about her wartime persecutors any more. “They were who they were.”

Prof Van Es says it was an “intense” journey into his own family history.

And as he researched the places where Lien had lived and hidden “the ghosts of the old Europe seemed very present”.

The Cut Out Girl by Bart van Es is published by Penguin Books.